A Shot in the Arm for German Orthodox Liturgy

It is often sad to see. Whereas the majority of the post-World War II communities representing the traditions of European Jewry have experienced sustained and escalated growth in number and strength, German Orthodoxy has for the most part been on the decline, after its initial successful transplantation and robust blossoming in various lands after the War. The burgeoning yeshivish and Chassidish communities, whose exceptional vibrancy and mushrooming has been duly noted by sociologists and statisticians in numerous studies, stand in stark contrast with most contemporary German Orthodox communities, the majority of whose members have assimilated into yeshivish or Modern Orthodox life, usually retaining at most a mere inkling of the customs, outlook and overall uniqueness that has marked German Jewry for a thousand years. Yes, there are those who have held fast and exactingly perpetuated the German Jewish traditions, but they are the clear minority.

What happened? Why is it that a Satmar chossid who moves out of Williamsburg will undoubtedly move to Kiryas Yoel/Monroe, and a yeshivish family that leaves Flatbush (Midwood, to be proper) will move to Lakewood or the like, as they feel a need to be part of a community where their specific traditions are preserved and lived, whereas German Orthodox Jews so often willingly assimilate into other Orthodox milieus without second thought, hardly retaining much of their heritage? Or, better yet, why is it that Chassidish and Sephardic talmidim at Litvishe yeshivos retain their distinct ways, while they absorb and fully immerse themselves in the high-caliber learning at these yeshivos, whereas the same retention of original group identity is not usually found among German Jews who enter the “outside” yeshiva system or other differing venues of Orthodoxy? (No, this article is not an attack on German Orthodoxy. On the contrary, I am pained by its decline and the deterioration of its beautiful legacy. A sizable percentage of my own lineage is of German extract; I am not an outside critic.)

I believe that the issue ultimately boils down to the historical, centuries-old religious destruction wrought by the Reform movement (and the general phenomenon of assimilation) in Germany – destruction whose impact was more profound and far-reaching than perhaps realized.

In Rav Breuer: His life and Legacy, Dr. David Kranzler and R. Dovid Landesman explain the abject levels of ignorance in many Orthodox communities in Germany during the previous century, as a direct result of Reform’s successful dismantling of the traditional chinuch (Jewish education) infrastructure. The former homeland of so many Gedolei Ha-Rishonim, preeminent Medieval Torah authorities, was reduced to a locus in which many Orthodox rabbis had no choice but to tell their congregants stories, rather than deliver shiurim, note the authors of this important book. Whereas the monumental efforts of luminaries such as Rav Samson Raphael Hirsch, Rav Azriel Hildesheimer, Rav Dovid Zvi Hoffmann, Rav Salomon Breuer and others had a seismic impact on their immediate communities and institutions and far, far beyond, there was so much damage that needed to be addressed, such that it was simply not possible for these and other stars of German Orthodox renewal to totally undo the systemic religious destruction and deterioration throughout the country.

The effects of Reform impacted German Orthodoxy at the highest levels, as evidenced most glaringly by major pre-War German communities’ engagement of Torah authorities and rabbinic leaders from the East, the most notable of whom were Rav Yechiel Yaakov Weinberg (the Seridei Aish) and Rav Markus Horovitz. (Rav Weinberg distinguished himself in Germany well before being elevated to rabbinic leadership there, yet German Orthodoxy itself had at the time not produced many others in his likeness.) There were few yeshivos in Germany and a handful or two of major indigenous Orthodox leaders, as the impact of Reform was pervasive on so many levels, including that of Torah scholarship.

It is against this backdrop that we can perhaps view the relatively recent stagnation and atrophy of much, but certainly not all, German Orthodox life. It is clear that for the better part of the past few centuries, the highest echelons of Torah learning were to be found in Eastern Europe; many families in Germany, including those of Rav Shimon Schwab and a good number of others in Frankfurt am Main (as well as the family of one of my rebbeim, from Baden, Germany) sent their sons to the East for yeshiva study. In fact, I remember my maternal grandmother, whose father originally hailed from Beelitz, Germany, relating to me how she recalled her father telling her as a girl about the many prestigious yeshivos in Lithuania. The center of Torah had moved definitively to the East, as assimilation and Reform did their best to minimize it in the West. Hence can we perhaps understand the relatively recent and contemporary trend of large numbers of German Orthodox Jews shifting affiliation toward the yeshiva movement and its lifestyle, as once these people got a taste of higher Torah learning in their original communities, they gravitated to its obvious epicenter and did not take along with them their native group identities, perhaps lacking the confidence or appreciation to retain their own mesorah (tradition) while simultaneously steeped in a first-class Eastern European learning environment. And, in the opposite direction, those German Orthodox Jews who were not exposed to a more advanced or intense Torah learning experience may not have fully grasped the profound significance of holding fast to one’s own unique traditions and Torah leadership, and therefore following the crowds out of German Orthodox kehillos (congregations) was not well recognized by these people as the abandonment of an important mesorah.

In any case, it is painful to witness the voluntary dissolution/implosion of much of German Orthodoxy. The more one learns Torah and studies liturgy, discovering therein the beautiful, deep and ancient bases and traditions of German Jewish religious practice, the more acutely one acknowledges the loss.

However, there is yet a bright side of the picture. While it is true that some German Orthodox Jews and congregations have heroically and steadfastly resisted the forces of this internal assimilation, thereby preserving their heritage and even their weltanschauung, there is now a renewed interest on the part of many to perpetuate and disseminate the legacy of German Orthodoxy.

The main organ involved in this effort is Machon Moreshes Ashkenaz/The Institute for German Jewish Heritage, whose network of shuls, publications, nusach (liturgical rendition) projects and educational programming has achieved great popularity and acclaim. Yet there are also individuals throughout the globe, whose private initiatives to perpetuate and enhance the heritage of German Orthodoxy have yielded first-rate works that should not go unnoticed.

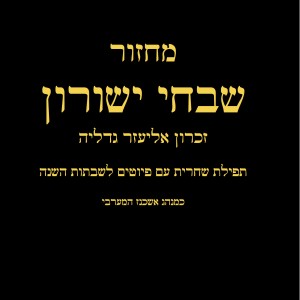

The latest such work is Machzor Shivchei Yeshurun, which features a complete, year-round selection of Western Ashkenazic piyyutim, with rich, historical background and thematic commentary, as well as halachic insights and explanations of various minhagim. This exquisite work, co-published by Goldschmidt Basel AG/Rodelheim, is the product of Rabbi Dovid Roth, along with his team of experts, and it carries the important approbations of Rabbi Binyamin Shlomo Hamburger, who heads Machon Moreshes Ashkenaz, and Rabbi Arie Folger, whose masterful Western European rabbinic leadership is accompanied by his vast and intense knowledge of that region’s liturgy and customs. Each of the approbations is a detailed and elaborate essay about the origins and halachic significance of piyyutim – each a unique must-read piece. (I also urge readers to consult Rav Soloveitchik’s discussion of piyyutim on pages 76-77 here, and elsewhere.)

Machzor Shivchei Yeshurun also features a beautiful and elaborate exploration of the structure and categorization of piyyutim, including charts that make it all quite simple (even for people such as I, for whom the world of piyyutim is pretty much like a foreign country). This 796-page mega-volume includes annotations and extensive supplemental notes, references to variants and other traditions, source citations and a lengthy appendix, and is presented in the form of a complete Shabbos morning siddur, so that mispallelim (worshipers) need not use a separate sefer of piyyutim in addition to their siddur. It’s all there, from Adon Olam/Birchos Ha-Shachar through the end of Mussaf, and everything that is recited in between, with brand new and beautifully formatted text. (Please click here to view a few sample pages. The introductory price is $18 for pickup purchase from local distributors; the online price includes shipping.)

May the author of Shivchei Yeshurun and his team see great success with this important publication, and may the entirety of our people appreciate and perpetuate our sacred traditions.

I live in Beitar Illit, and am a member of what is colloquially known here as the “Yekke Minyan” (more formally, Kehilla Adas Yeshurun). Many Yekkes who have fallen into the trap you describe (of abandoning their beautiful heritage) must feel some sense of shame in the same. Why do I say that? Because they don’t simply remain neutral. They actually poke fun (and not gentle needling) at the minyan and Yekke minhagim (while they are perfectly happy waiting three hours between meat and milk).

We are celebrating our 11th anniversary on, I believe, Parshas Vayakhel/Shekalim, March 11-12. HaRav Hamburger will BE”H be attending and speaking. All are welcome to join us on this occasion.

Note that Goldschmidt in Switzerland has also been publishing various siddur and machzor editions that were originally published in Roedelheim, Germany. These include editions edited by Wolf Heidenheim. Some also contain German or English translations.

R’ Gordimer, this is one of the better treatments of German Jewish heritage that I’ve seen in recent times. In addition to your important work on OO, I would love to see more analysis of the (lack of) Yekke mesorah in practice today. Please continue to elaborate on these thoughts so that we can bring this issue the attention it deserves!

As a descendant of a lapsed Yekke myself, I understand the angst spoken of by Rabbi Gordimer.

There is no question that a large portion of the blame must be laid at the feet of the early German Reformers. I think. however, that there is another, less sinister force at play too. I refer here to the lack of a central community due to the fact that Breuer’s – the mother ship of the Yekke community – is located in a neighborhood that is impractical and unaffordable. As it is, it’s hard enough getting kids ot move back to their old neighborhoods, but it’s even less likely when the neighborhood offers few apartments [no homes!] and at rents that are astronomical.

When home base is inaccessible, it’s little wonder that the community loses it’s identity in a generation or two.

One can’t forget the impact of Naziism on World Jewry. It is tough to respect a Yahadus whose leaders worshiped German culture knowing what happened.

Of interest SRH’s hashkafa is followed by many around the world but people do not associate it with SRH-tough to take as hashkafic hero one who gave a sermon on a birthday of a poet.

Of course, one can’t forget that KAJ itself by taking a Rabbi who rejected SRH’s hashkafa-claiming it was a horaas shah implicitly rejected German thought for Eastern European hashkafa. The revisionism of a gadols belief on one side of Washington Heights would be an example to be followed

One should not underestimate the influence of the Mishnah Berurah in formulating standard halachic practices throughout the Ashkenazic world. In addition, most communities outside of Brooklyn are an amalgamation of people with varying minhagim, and for the sake of cohesion, shuls have to create consistent, common, and most widely-practiced standards. A similar phenomenon occurred in Israel with the standardized nusach of tefila.

The Western Ashkenazic tradition is alive and well in Anglo-Jewry, including the distinctive leyning which is standard throughout Britain. Those interested in discovering more are welcome to visit our lively communities.

Both the USA and England received approximately the same number of German Jewish refugees (approximately 80 – 100, 000) between 1933 and the start of WWII. In England they caused standard Nusach Ashkenaz to switch from Litvish Minhag to German Minhag, but Not in the USA. That’s because in England they now constituted about 1/3 of the British Jewish population, while in the USA it was closer to 2%. Additionally, Engalnd allowed in all the German Yeshiva bochrim and Orthodox Rabbis, while the USA didn’t. (No German yeshiva bochur was unable to escape to freedom.)

“Additionally, Engalnd allowed in all the German Yeshiva bochrim and Orthodox Rabbis, while the USA didn’t. (No German yeshiva bochur was unable to escape to freedom.)”

No-clearly untrue-there are examples of those who were studying in German Yeshivot who emigrated to US after Kristallnacht.

Thanks. My language was confusing. To clarify: The UK allowed in all the German Rabbinical students, while the USA didn’t allow all in , just some.

I don’t know where your info about the UK are from, but the numbers of refugees you cite seem far too high. I was born and raised in the UK, and can tell you the proportion of pre war German refugees as is far smaller than a third. I doubt it’s more than 10%. Most UK Jews are descended from Eastern Eurpean immigrants pre WWI. And the nusach definitely didn’t change, it was never Litvish, always German due to a quirk of history from the 1700s onwards. Hamburg in fact. The same standard siddurim were used all the way from the 19th century by most communties until the rise of the Artscroll siddur in the last 20 years or so

‘Hamburg in fact’

Sorry, Leipzig IIRC

It is easy enough to look up how many German Jews emigrated to UK in the 1930’s and then look up the total Jewish population of UK at the time and do the math.

R’ Shmuel – Baruch she’kivanti. Immigration from Germany to the UK was 40,000 according to 2 different sources I found, and total Jewish population was about 400,000. So 10% as suspected.

I’m still intrigued as to where you saw that the nusach changed .

I was told that by a wonderful Jewish businessman from London whose father was a German Chazan. Perhaps my guest was wrong. I’m open to your perspective.

R Shmuel – Thinking it through again I suspect that your acquaintance may have been talking about a particular shul or two where that happened. The German immigrants tended to be either very shtark, which was the minority, or very unobservant, following the pattern in prewar Germany. The pre-existing UK community was fairly homogenous in having a big Jewish heart but little Jewish literacy or observance on average. So the shtark Yekkes tended to focus around a few shuls which were not part of the mainstream communal organisation. Perhaps in a few frummer than average shuls where there was a large influx of yekkes, percentagewise, the nusach changed.

Which leaders are you talking about? The Rabbis in Germany fought bitterly against the Reform movement and the German culture they represented.

People who leave their masoreh, they actually follow the Reform and the German culture on their own…

“It is tough to respect a Yahadus whose leaders worshiped German culture knowing what happened. Which leaders are you talking about”

RSRH for starters

Worship is a very strong term. Talking about RSRH as worshipping German culture is wildly inaccurate. He was clear and consistent about Who we worship and that our values are derived solely from Torah. In fact that’s his hallmark throughout his writings. He certainly appreciated aspects of German culture, or really Western culture in general and and thought they had in place in chinuch. But worship? Certainly not.

And I don’t see why it’s hard to respect the legacy of RSRH. Major features of 19th Century German culture are no different to broader Western European culture, in terms of literature, music, philosophy, science, which is the basis of the Mada of YU after all. So I’m not sure why you’re opposed to that.

“Worship is a very strong term”

Fair enough

“He certainly appreciated aspects of German culture, or really Western culture in general and and thought they had in place in chinuch.”

Appreciate is not strong enough.See following:

Rabbi Hirsch’s attitude to German culture

Rabbi Hirsch’s attitude toward German was not the same as that of the

other traditionalists of his time who were conversant in that language.

To the latter, it was a language they knew and employed, but

nevertheless a non-Jewish language. Rabbi Hirsch, on the other hand,

had a deep emotional feeling for German and a strong attachment to

German culture that also went far beyond the modest requirements set

down by the conservative Maskilim who advocated practical subjects as

necessitated by social and economic considerations. Rabbi Hirsch had

been educated in a gymnasium focusing on humanistic studies.

Influenced by the atmosphere in his family who encouraged secular

studies, he appreciated the humanistic spirit which permeated the

German cultural climate as well as the aesthetics. In the first of the

Nineteen Letters, Rabbi Hirsch makes his imaginary protagonist

remark: “How can anyone who is able to enjoy the beauties of a Virgil,

a Tasso, a Shakespeare, who can follow the logical conclusions of a

Leibnitz and Kant–how can such a one find pleasure in the Old

Testament, so deficient in form and taste, and in the senseless writings

of the Talmud?” Before Rabbi Hirsch, no Orthodox Jew had ever

expressed such sentiments, even as a prelude to their rebuttal.

Rabbi Hirsch was especially influenced by Hegel and Schiller. In a

speech given in his school he founded on the centenary of the birth of

the latter, he claimed that the universal principles of Western culture

embodied in Schiller’s writings are Jewish values originating in the

Torah.”

from

http://seforim.blogspot.com/2009/08/meir-hildesheimer-historical.html

“And I don’t see why it’s hard to respect the legacy of RSRH. Major features of 19th Century German culture are no different to broader Western European culture, in terms of literature, music, philosophy, science, which is the basis of the Mada of YU after all. So I’m not sure why you’re opposed to that”

People do respect the legacy of SRH wo admitting it-he may be the most influential figure of the 19th century but almost no one admits it-suspect strongly due to the German issue.

I’ll grant that ‘appreciate’ may be not quite strong enough. But the only sentence indicating otherwise in that whole piece you quoted was ‘Rabbi Hirsch, on the other hand, had a deep emotional feeling for German and a strong attachment toGerman culture’ .

As someone who counts RSRH as a strong early, and indeed enduring, influence in the process of becoming shomer mitzvos, I must say the German issue never troubled me at all. And I don’t believe I’ve ever come across anyone who has an even slightly Hirschian weltanschaung who has expressed distaste for RSRH’s world due to the German connection. That’s a sample size of 1 but anecdotes can be revealing.

Maybe it’s a generational thing. My generation (thirtys/fourtys) don’t have much if any animosity to things German that I’ve ever come across.

Rabbi Gordimer:

As usual, I am touched by your beautiful love for and sensitivity towards Mesorah.

However, the decline of authentic German Kehillos has not taken place in a vacuum. It is not just the German Kehillos. My paternal family is Hungarian Ashkenzic. Where are those Kehillos today?

Vien, Nitra, Pupa, Tzelem, etc…, which were Ashkenazic, have become completely chasidish.

The Litvishe Yeshivos are primarily populated by descendants of Hungarian Jews.

The piyutim don’t speak to us today because we don’t understand them, plus, we won’t recite them without understanding them like our grandfathers or great grandfathers did. Plus, the yeshiva world skips them as do the young Israels.

“Vien, Nitra, Pupa, Tzelem, etc…, which were Ashkenazic, have become completely chasidish.”

In terms of Vien and Nitra, those words are not correct.

Vien branches in Boro Park and Monsey daven Ashkenaz. Even at the first branch in Williamsburg, which mostly went over to Sfard a few years ago, there is still at least one (early) minyan that davens Ashkenaz.

Various Nitra branches also daven Ashkenaz, such as the one in Boro Park, for one example.

There are other outposts of Hungarian Ashkenaz that persist as well.

While it is definitely true that there has been some Hassidification, Hungarian Ashkenaz has not totally disappeared, despite what some people would like you to believe.

My point is that even if several of them still daven nusach Ashkenaz they dress like chasidim, their leaders are not longer called Rabbonim, but REbbes, etc….

It is more complicated than that. The tzibbur is not monolithic.

Visit some of the old Oberland minyonim/botei midrash and you will see for yourself. I wonder if you have actually done so in recent years, as I have.

It is important to see the actual reality with your own eyes, rather than relying on sometimes slanted reports.

I would love to. Can you recommend a couple for me to visit?

It isn’t monolithic, but Shmuel Landesman point that a large segment of the Oberlander kehilos, probably a majority, has adapted Chasidish minhagim, terminologies, modes of dress, etc. is essentially accurate.

“The Litvishe Yeshivos are primarily populated by descendants of Hungarian Jews.”

Source for that claim?

Are you claiming that for R. Gordimer’s yeshiva as well (Yeshivas Rabbeinu Yitzchok Elchonon)? While it may be true in some cases, the background of talmidim can vary substantially in different locations and institutions, so such sweeping generalizations should be handled with caution.

Only 7% of Jews in Lithuania and 1.6% of Jews in Poland survived the Nazi conquest. About half of Hungarian Jews survived. (I understand it’s because the Nazis didn’t invade Hungary till 1944, while the first 2 countries they invaded in 1939 and/or 1941.)

I suspect it’s less so at YU.

The statistics given (which require some adjustment, e.g. especially re Poland) are only part of a picture. There were other Jews who emigrated in earlier decades as well, for example.

There are also many people who have mixed roots. Such unions became a lot more common after war and migration. If a talmid is a child of a marriage between Hungarian and Polish then, how is he classified? Product of a Polish-Litvish union?

{The statistics given (which require some adjustment, e.g. especially re Poland) are only part of a picture. There were other Jews who emigrated in earlier decades as well, for example.

There are also many people who have mixed roots. }

The statistics are from “Eyewitness to History” by Ruth Lichtenstein.

I personally have mixed roots and descend from Jews who emigrated from earlier decades.

I was just explaining how Litvaks are a small minority today in Litvishe yeshivos.

I think a main reason for the assimilation of German-American Jewry into yeshivish/Modern Orthodox circles is a simple one: they are just not that different from those communities – the same way that Jews from Hungarian, Lithuanian, Polish, and Russian origins have become more or less indistinguishable from one another today.

Chassidish and Sephardic Jews are far more different sociologically, culturally and religiously from general Ashkenazi Jewry, and have thus retained separate communities.

I suspect it’s down to the way culture works. Culture is a really deep embedded collection of subtle, and not-so-subtle, behavioural and emotional responses shared by people from a particular community. Some cultures are very deeply embedded and people actively look to mix with people of similar culture. That’s certainly true of sephardim. Chasidim have the added impetus of the ideological centrality of community and the Rebbe. Other historical communities had a culture which turned out to be less deeply embedded and most Yekkes found themselves merging into the general ashkenazi world through lack of cultural impetus not to, regardless of their particular tunes and minhagim. It takes a really dafkanik to maintain minhagim in the face of cultural assimilation, and most yekkes found they just weren’t as dafkanik as they were reputed to be…

Or to put it another way, take a yekke out of Germany and the culture won’t last another generation, because the culture was just a feature of one place and time.

By the way it’s not just just the yekkish culture and minhagim which have disappeared. The current ashkenazi world of minhagim is a post war conglomeration of bits of different pre war communties, more Litvish (in the actual old Lithuanian sense) in the charedi yeshivas, more yekkish in the UK, baalebatish America has developed its own set of norms, and more Gra-like in E’Y. But there’s really nowhere which solidly retains the minghagim of Vilna , or Hamburg, or Warsaw etc etc.

I am certainly no expert, but it occurs to me that German orthodoxy had multiple strands going back (significantly prior) to the generation of RSRH ztl whose contemporaries both Rav Hildesheimer ztl and Rav Bamberger ztl were openly and critically at odds with his POV. I don’t know how their positions reflected forward. The bias against both of these Torah giants in the eastern European world is not insignificant.

In more modern times, it is clear that the rigors of academic talmud, require broad familiarity that few develop outside the yeshivah; I am in awe of those who develop such expertise otherwise. Both RYYW ztl and Rav Kaplan ztl are prime examples of gedolim who added significant academic perspective to their backgrounds developed at slabodka as they transitioned to Hildesheimer. The German rabbinate required a much broader set of intellectual and other skills that did not allow German rabbis to develop the deep but narrow skills of Lithuanian talmudists. Is that a result of having to compete with the reform movement? Very likely, but more broadly perhaps the result of a changed environment outside of just the Reformers.

I find it interesting that Slabodka’s most talented talmid was so attracted to academic methods. Had he lived, RYK ztl thought he would have revolutionized the derech haLimmud.

It also significant that Rav Schwab ztl (for a long period) redefined RSRH. Despite its clearly acknowledged revisionism, its impact appears to have taken hold in the Breuer community.

Well before this siddur you highlight that I look forward to getting, I received as a gift a reprint of a siddur published in Germany in 1925 by Rav Bulka ztl’s father, which I cherish. I may be foolhardy, but I have such respect for such efforts that I value the places where it differs from other texts.

“I am certainly no expert, but it occurs to me that German orthodoxy had multiple strands going back (significantly prior) to the generation of RSRH ztl whose contemporaries both Rav Hildesheimer ztl and Rav Bamberger ztl were openly and critically at odds with his POV. I don’t know how their positions reflected forward.”

Probably Rav Hildesheimer had more followers of his viewpoint in orthodox Germany than SRH had of his. It is my impression that was true until the Holocaust

“It also significant that Rav Schwab ztl (for a long period) redefined RSRH. Despite its clearly acknowledged revisionism, its impact appears to have taken hold in the Breuer community”

So much so that I have spoken to some who went to their day school through 12 and could spend all their years there wo hearing anything about SRH.

“Well before this siddur you highlight that I look forward to getting, I received as a gift a reprint of a siddur published in Germany in 1925 by Rav Bulka ztl’s father, which I cherish”

It is my impression that in general what we refer to as Yekke minhagim reflect those of Northern Germany-Southern Germany in tfilah followed much more closely to standard Ashkenazic practice.

There had, in the past, been efforts to establish a KAJ kehila / shul in the Boro Park/Flatbush vicinity. I’m not sure why it didn’t work out but it is certainly still a worthwhile endeavor as many of the Yekkesh community do reside in that vicinity.