Faith, the Final Frontier

by Brian Keating

As a professor of astrophysics, you might be shocked to learn I don’t believe in the law of gravity. I don’t believe in black holes either. I don’t even believe that the Sun rises in the east.

I don’t believe any of these things because I don’t have to…I have evidence for them. For centuries, scientists have used evidence to test their ideas of the physical world. It’s called the scientific method and it’s the most powerful knowledge generation tool ever invented.

In contrast, it’s common to use words like ‘belief’ or ‘faith’ when discussing God. Although the universe seems designed for our existence, even the faithful admit that’s not indisputable proof that a Designer exists. They take it on faith. Because of the lack of cold, hard data it’s probably not surprising that over 70% of the National Academy of Sciences, the most prestigious association of scientists in the United States, do not believe in God.

So, how do secular scientists account for our existence without a Creator? Many cosmologists believe the explanation lies in a new theory called the multiverse. According to these scientists, what we used to call ”the universe” is not the whole enchilada…far from it. In the multiverse theory, our universe is accompanied by not just one or two other universes, but perhaps by an infinite number of other universes, most with properties nothing like our own. Some would be too cold for life like us to develop, some too hot. But, with an infinite number of possibilities, some would be just right.

To supporters of the multiverse, our existence is an accident that was bound to happen in the capacious cosmos. What’s surprising though, is that even scientists who believe in the multiverse admit there’s no hard data supporting it.

How is a scientist supposed to evaluate an idea for which there is no evidence? In 1959, Karl Popper devised a way to test if an idea was truly scientific, or if it was pseudo-science cloaked in technical dressing. He said if there’s no way to disprove a claim, if it can’t be falsified, it’s not science. Originally, Popper’s bete noir was astrology, whose practitioners divine the fate of individuals from the positions of celestial bodies on their day of their birth.

Popper noted that astrologers’ predictions were so nebulous that nothing could falsify them. Here’s a typical horoscope for me, a Virgo, “Today will bring an unexpected challenge”. Such a prediction is so imprecise, it’s bound to be accurate; not only for my sign, but for the other eleven as well. Popper said, “It is a typical [astrologer’s] trick to predict things so vaguely that the predictions can hardly fail… Those among us who are unwilling to expose their ideas to the hazard of refutation do not take part in the scientific game.”

Sadly for Popper, nowadays, newspapers still devote more ink to astrology than they do to astronomy. The reason for this is simple: people are naturally biased to believe vague, but accurate, explanations of their fates, especially when it comes from an authority.

Despite stereotypes to the contrary, we scientists are people too. We sometimes want to believe things that comport with our own theories and discard discordant data, a phenomenon known as confirmation bias. Scientists also represent society’s most revered authorities. Unfortunately, the combination of authority bias and confirmation bias is leading to some pretty unscientific effects, especially when it comes to the biggest theory of them all, the multiverse.

Take Nobel laureate Steven Weinberg. To Weinberg, the multiverse’s infinite vastness is good news, offering a reason why “we find ourselves in a universe favorable to life that does not rely on the benevolence of a creator, and so if correct will leave still less support for religion.”

But this is also the bad news when it comes to the scientific method. For, as physicist Paul Davies. Davies said, “Invoking an infinity of unseen universes to explain the unusual features of the one we do see is just as [made up] as invoking an unseen Creator. The multiverse theory may be dressed up in scientific language, but in essence it requires the same leap of faith.

Since any data, even the absence of data, is consistent with the multiverse, this model of cosmogenesis is immune to falsification. Because of this, some of its detractors call the multiverse a “theory of anything”, reminding me of GK Chesterton’s quip, “When men stop believing in God they don’t believe in nothing, they believe in anything”. In the case of the multiverse, Chesterton’s wisecrack is literally true: the very same scientists who reject God’s existence due to insufficient evidence have placed their faith in a theory which seemingly neglects the scientific method.

To be fair, there are few proposals out there to test the multiverse hypothesis and some say it’s just a matter of time before evidence is found. But be wary when a cosmologist tells you to be patient: it might take a billion years before we know the answer. Until then, cosmologists must keep the faith.

Now as cosmologists struggle to explain the universe we see, to explain the very existence of time, space, and even life, scientists should be take an candid accounting of their motivations for supporting the theories they support. If they can do so honestly, there’s hope they can remain in Popper’s scientific game. Otherwise they might just be taking a huge leap of faith.

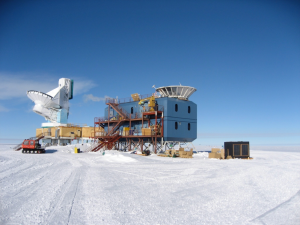

Brian Keating, an observant Jew , is Professor of Physics at UC – San Diego. He designed and built the BICEP telescope, optimized to peer back to the very first moments after the Big Bang. His exploits at the South Pole, where the telescope was placed, are chronicled in his new book, Losing the Nobel Prize: A Story of Cosmology, Ambition, and the Perils of Science’s Highest Honor.

Not only isn’t there evidence for the multiverse, there cannot be direct evidence of the idea. By definition. If we did interact with this other region, it would be part of this universe and those interactions part of our physics, and not another universe at all. All that could be found, such as in Hawking’s last paper (edited a week before his death), is evidence that our universe did or didn’t start in a state consistent with a multiverse theory. It can only show consistency or inconsistency between two theories — one about cosmogony (Big Bang and Inflation) and one about what kind of multiverse we’re in.

So, bottom line, the multiverse is theology — it is the positing of an infinity whose existence could never be proven (rather than indicated, suggested, consistent with data…). The only difference is that belief in the multiverse makes no moral demands. This willingness to not only embrace one theology but consider it scientific speaks volumes about Rav Elchanan Wasserman zt”l Hy”d’s position that if we were able to think without emotional bias, belief in Hashem would be the default position for humans. But we’re not able to. On big questions like religion, the mind serves to justify conclusions the heard already reached.

So is the implication that we each “believe” in whatever gets us through the night?

Kol Tuv

Was that question to my comment, or Brian Keating’s essay? If the former…

I am just saying that making an assessment of non-trivial logic gives much room for a person’s unconscious biases (negi’os) to wiggle in. And despite my mention of R Elachanan Wasserman, I don’t only mean our wanting license for physical or other improper desires. (אמר רב יהודה אמר רב: יודעין היו ישראל בעבודת כוכבים שאין בה ממש, ולא עבדו עבודת כוכבים אלא להתיר להם עריות בפרהסיא – סנהדרין סג ע”ב) That also includes our need to feel that we weren’t wasting the time and effort already invested in a cause. And loftiest of all: Man’s search for meaning. We have biases toward believing that which makes us feel like we’re living meaningfully no less than those that allow us to satisfy our more animalistic or egoistic desires without guilt.

When we assess an argument, how do we decide whether or not the postulates it works from are self-evident or questionable? Whether the logic is elegant or flawed? Whether an unanswered question is an interesting puzzle or an argument shattering disproof? Our reason ends up flotsam in a turbulence of motives.

Too many decades ago when I was still in high school (and an Orthodox Jewish one at that), I remember posing the idea of multiverses in response to my Rabbi teacher presenting his evidence for G-d’s Existence. So the Rabbi said that there is no point in supposing such a thing, when there is no evidence for it. So you see, exchanges like the above are not necessarily anything new. King Solomon was so right when he observed that there is nothing new under the sun.

The other day, I came across a quote by Aldous Huxley that managed to catch my attention. He basically said that people often make the mistake of thinking that atheists somehow have pure motives, that they come to their conclusions through rational discourse as they arrive at their conclusions in a totally objective way. But this would be so much at variance with the real truth. Apparently, said Huxley, some people wish to deny G-d’s Existence, because then they can engage on unbridled sexual escapades without having to answer to a Higher Power. And that may ultimately be why the world resents us Jews so much. By bringing G-d to our world, we also brought moral conscience to our world, and if there is one thing that almost all people wish to avoid, it is being held morally accountable.

Science can explain physical phenomena. Science cannot explain metaphysical issues and beliefs except by engaging in scientism which denies the existence of the metaphysical

Wrong dogmatic assumptions can lead to needlessly complex explanations:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deferent_and_epicycle