Rational, Irrational, and What’s Between

Half of the art of a good polemicist is attaching an effective label to his argument. My good friend Rabbi Dr Natan Slifkin found a winner in calling his approach “rationalist Judaism.” Who doesn’t want to see himself as rational? Measured by the success of his blog by the same name, Rabbi Slifkin has succeeded in attracting a large readership. Only research could tell us how much of the response is baruch Mordechai, and how much is arur Haman. In other words, are people looking for a new approach, or are many simply fed up with what Rabbi Slifkin sees as egregiously non-rationalist approaches[1] that have taken hold in parts of the Orthodox community. Even not on Purim, there may not be that much of a difference.

I am not going to disagree here with his central thesis: that there is a viable, self-contained approach to Torah Judaism that downplays or completely dismisses mystical elements. It is not my Yiddishkeit, but I don’t have a veto over what people believe. He can point to important figures in the rich (and varied!) hashkafic literature going back to the times of the Geonim and Rishonim who might be associated with such an approach. But good arguments sometimes resemble minefields. One misstep and things start blowing up. People who roll that delicious self-description of rationalist Judaism on their tongues can – and often do – extend the arguments, and arrive at conclusions that simply do not follow. I would like to call attention to some of the places that the intrepid reader of Rationalist Judaism might falter, with disastrous consequences.

You may have noticed the opening three words of the essay. Don’t dismiss them as an empty exercise in civility. Rabbi Slifkin and I are indeed good friends, and have been for many years. I was his shadchan. I penned haskamos for several of his works, including the most controversial ones. I refused to recant those approbations. I believe that I am more aware than most of how much good some of those books accomplished, how they preserved the Yiddishkeit of so many bright, frum, souls. His approach to evolution is still the single best work I know of for people who see evolutionary thought as an obstacle to their full observance. He, in turn, has kept me on the Board of the Biblical Museum of Natural History. Over the years, our Torah world views have grown somewhat apart – but not our friendship. As much as I disagree with elements of his approach to certain issues, I just as much believe that the friendship of frum Jews who disagree with each other is exactly what HKBH expects of us.

The most dangerous misstep that one can take is to confuse non-rational with irrational. They are not the same. Non-rational approaches make use of assumptions and vocabulary that are less immediately obvious than those of rational approaches. The rational purist finds them unacceptable and unconvincing. The non-rationalist accepts kinds of evidence that many thinking people would not find adequate in arenas of thought outside of Torah hashkafah. Irrational approaches, on the other hand, are very different. They involve logical contradictions and impossibilities, like positing that certain quadrilaterals only have three internal angles. The rationalist, then, is entitled to find assertions of the non-rationalist to be implausible – but not impossible.

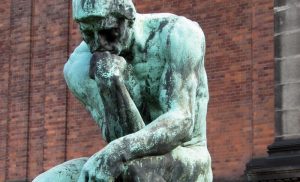

It is also important to realize that insufficient evidence does not mean no evidence at all for the non-rational approaches. Those who follow them – myself included – accept as evidence the sheer number of Torah luminaries that embrace them. We trust the chachmei ha-mesorah – in this case, probably the vast majority that have had a major impact over the generation. We trust them not only within the narrower confines of pure halacha, but in how to think and emote as Torah Jews. Reasonable people can disagree about whether to find intellectual safety in the company of so many others, but those who do are not accepting the irrational. They disagree about the strength of some kinds of evidence. The non-rationalist does not dismiss human logic as worthless. People who buy into overt logical contradictions, on the other hand, can be justly criticized for dismissing rational thought – what some of our Rishonim saw as the tzelem Elokim – the very image of G-d. Someone who accepts the evidence behind non-rational Judaism cannot be accused of the same.

Another fallacy that can result from improperly digesting Rabbi Slifkin’s posts is that Rational Judaism is…rational. It can’t be entirely so. Rabbi Slifkin firmly believes in Hashem, and is fully observant. But belief in a Higher Power who is not bound to the laws of Nature isn’t entirely “rational” to those who reject any belief that cannot be sustained by empirical evidence.[2] Belief in G-d, they argue ( (ע”לis as attractive as supporting the Flying Spaghetti Monster. A dogged insistence on eliminating everything other than the empirically knowable just doesn’t work well with revealed religion. The rationalist can move away from leaps of faith, but smaller investments of that faith will remain necessary.

Moreover, it cannot be demonstrated that, of the two choices, rational Judaism is a priori better or superior to the non-rational forms. Insisting on certain kinds of evidence may very well be the best way to do science, but it can be stultifying and confining as well. Much of our personal experience cannot be shared, proven, or replicated. As many have observed before (especially Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks in our day), science can tell us the “how” of existence, but not the “why.” It also cannot tell us much about some to the ideas that are most important to us, like love, goodness, loyalty, and kindness. The Ramchal writes that one of the reasons that Hashem made theurgic phenomena real is to ensure that people would not be so smug as to believe that their human understanding could apprehend everything around him. He purposely designed phenomena that conflict with his reason, so that he should not give reason more prominence than it deserves.

Related to his is the claim that rational approaches are better, because they appeal to our common sense. But “common sense” often comes up short because the obvious turns out to be wrong, and because some things cannot be understood through “common” tools, but require much background and sophistication – often, in a non-intuitive manner. Common sense had people believe that the earth was at the center of the universe, surrounded by celestial bodies travelling in circular paths. Or that there was force over distance. Or no force over distance. Parts of quantum mechanics have struck writers as in synch with Eastern mysticism, or simply contrary to expectation – even though correct.

Perhaps most importantly, it is a fallacy to think that the choice of rational or non-rational is binary. There is a huge continuum on which these positions fall, and an infinite number of points between the end points. The Jew who rejects the limitations of a rationalist Judaism does not necessarily conclude that revelation is superior to reason, and that since he cannot understand everything, he will not try to understand anything. We have a rich tradition of mechabrim who fully accepted the mystical tradition, and endeavored to translate as much of it as possible into less mystical language. The Maharal and Ramchal certainly belong to that tradition.

There are two take-aways from this discussion, I believe. The Jew who does not see himself in synch with the approach of Rationalist Judaism need have no hesitation about buying into an inferior product – low culture Judaism, as it were, relative to high culture. That just isn’t so. We should also understand, however, that for many G-d fearing, wonderful Jews, Rationalist Judaism is a lifesaver, and a legitimate way for them to serve Hashem.

-

Some readers will find this designation jarring or offensive. I use the terms “rational” and “non-rational” simply for making this essay easier to read, by accepting Rabbi Slifkin’s choice of words. By using it, I do not imply that I accept it as the best description of what I believe in myself, and endeavor to teach to others. ↑

-

While many in the Torah community accept the existence of “proofs” of G-d’s existence, many do not. There are firm maaminim bnei maaminim who have other reasons to believe, without seeing those reasons as self-evident and logically dispositive. They refuse to equate heresy with logical error – but they still reject heresy. This is not the place for developing this idea. ↑

Rabbi Adlerstein, you freely interchange the words “rationalist” and “rational.” But on my blog, I am very careful to differentiate between them!

I agree with RNS’s comment above — it is incorrect to confuse “rationalist” with “rational”. Of course, no Orthodox Jew could be fully rationalist, as there is no evidence other than authority for the events of Yetzi’as Mitzrayim and Matan Torah. Similarly, none of us can be fully mystical even in disagreement with reason, like Tertullian’s credo, which ends “… certum est, quia impossibile” (“it is certain, because it’s impossible”).

For that matter, there is a disjoin when speaking of rationalism and not speaking of which era’s definition of the term one is using. For example, the Rambam was a rationalist, because in his day rationalism meant Natural Philosophy, and expecting the universe to be reasonable and elegant. Much of what he writes is based on whether Aristotle proves his point philosophically or not. Without any recourse to experiment — for the simple reason that experimentation and scientific method hadn’t been invented yet. By today’s standards of rationalism, the Rambam wouldn’t qualify. Meanwhile, Rabbi Yehudah haLevi, who promoted a variant of Reliabilism rather than Proof from First Principles was not considered a rationalist in his day, but post-Kant his words are well in the rationalist tent. (Far more so than belief in the value of Philosophical Religious Proof. Thinking that people are capable of avoiding personal bias well enough to distinguish valid proofs from flawed ones is a downright mystical idea.)

Then there are the generalizations we make about what kind of hashkafos a rationalist or a mystic would hold, which really don’t work when looking at actual rabbanim. For example, the Ramchal was a rationlist mequbal, the Maharal was a mystic who didn’t teach anything like Qabbalah, and the Leshem makes a strong case for saying that the Rambam and the Ari give two models that describe same metaphysics!

Talking about rationalism vs mysticism blurs many topics into one distinction, and equivocates between different definitions of the terms. And since no Jew can be at either end of the axis for which the distinction is being suggested, the whole enterprise of defining “Rationalist Judaism” is about drawing self-contradictory sets of lines in the middle of a big gray area.

is not the biggest concern that those who believe in the non-rational approaches have made them a sine qua non

of ‘Torah Judaism’ , and write out as apikorsim those who say otherwise?

The completely different approaches of the rationalists and the non rationalists can be exemplified by two different approaches of middle age Jewish writers who each still have great influence the Rambam the rationalist and Rav Moshe de Leon the mystic

“Another fallacy that can result from improperly digesting Rabbi Slifkin’s posts is that Rational Judaism is…rational.”

R. Slifkin confronts this in “Drawing the Line: Is Rationalism Futile?”(March, 2009), which is listed in the “Important Posts” section of his website.

It seems to me that Rabbi Slifkin is trying to bring balance to the Orthodox world as a whole after the controversy over his books(compare, and also contrast, with Dr. Steven Bayme’s, “At 18, YCT A Balance To Rightward Orthodoxy”, in other words, every action has a reaction).

Also, in the interest of balance, I think it would paradoxically help the cause of Rationalist Judaism to continually make use of the advice in the Cross Currents “Comments and Tips Section”(originally a November, 2007 post by Rabbi Adlerstein) that “The harshest, most trenchant criticism can still be phrased in a more gentlemanly fashion….Close your eyes and imagine that you are in the Oxford Debating Society of a century ago.”

“The rationalist can move away from leaps of faith, but smaller investments of that faith will remain necessary…”

It may sound like semantics, but Rabbi Simcha Barnett, in a 2016 Project Inspire/Aish Hatorah video, says at the very most its a “skip of faith”, rather than a “leap” (“Online Kiruv Training – Jewish Misconceptions: Judaism is Based Upon Faith’, 1:38 in lecture).

I’ve also noticed a similarity in the Hebrew definition of “emunah” in the writings of both Rabbis Adlerstein and Slifkin. In “The Gospel of Judas and Jewish Faith”(April, 2006), R. Adlerstein wrote, “The word emunah loses too much when it is translated as “faith.” More properly, it has strong overtones of faithfulness and loyalty”. Earlier this year, R. Slifkin wrote similarly regarding the etymology, “or, you can opt to teach emunah as it really should be – not Discovery-style “proofs,” but rather loyalty (which is the true etymological meaning of emunah) to our sacred and wonderful mesorah.”(“An Aura of Respectability?”, January, 2018).

If our human reason is not the Supreme Reason, it should stand to reason (even ours !) that we can’t fully understand all phenomena in our immediate world and all others. There’s some element of “chok” even in what we feel we figured out. That’s not to say that its good to be irrational on purpose.

i believe that reducing what is irrational is a desideratum, at least for some like me. in every case belief will still be required. As prof. Halberthal has outlined in a number of lectures, we must take great care to understand and differentiate between a belief “that” as opposed to a belief “in” as opposed to a belief “as.” Traditional Jews should not fear to admit that we are believers in what cannot be rationally derived or logically proven. How that belief is delineated requires great care.

We must also be ready to admit that we cannot always articulate our beliefs in complete precision; beliefs are not subject to the same constraints as a mathematical or scientific statement. Attempts to articulate precisely can lead to irrationality.

Ain Haci Nami. There is much one can learn about Emunah and Bitachon from.our clasdical commentaries on Chumash who were not strictly rational the Baalei Chasidus Machshavah and Musar without intellectually boxing oneself into thinking that you have reached an answer as opposed to an approach.when Rashi and Ramban write more often that tbey dont know you are in very good company.

I am not entirely sure I understood the above, and so I am not sure that the comments that I am about to make are a rational response to this discussion about rationality, but I will give it a try.

Just like was said above, I am no different than most of us in wanting to think of myself to be of rational mind. In fact, to be honest, when people get too caught up in their emotions, or believe in truly absurd things, it really gets on my nerves. And for those of you who once upon a time watched television, I was a huge fan of Mr Spock on the original Star Trek series. Played by a Jewish actor who undoubtedly delved into his religious traditions to come up with many of his ideas, his character on that show was a man of pure logic.

Maybe I am a little slow, but to be honest, I never understood why Jewish mysticism is considered to be not rational. What is not rational about it? How is it any less rational than any other part of Judaism? From the little that I know about the Kabbalah, I just don’t see what is not rational about it. Am I missing something here? and btw, again I hesitate in what I am about to say, just in case I am interpreting his words wrong, but I spent over a year reading nothing but books by the great Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, and it is my distinct impression that he puts a very high premium on subjective experience, even considering it more important than the objective, empirical world. Or as my father told me long ago, Einstein may have been a brilliant scientist, but that does not mean that he was an expert in all other areas of life. I think of Stephen Hawking, whose scientific brilliance nobody doubts, that yet what an ungrateful fool he was regarding Israel. Just because somebody knows a lot about the physical world, does not necessarily produce wisdom.

But to return to the subject at hand, is our subjective experience not only as real, but even more real than our empirical experience? Because again from how I understand Rabbi Sacks, it is in our subjective experiences where G-d can be found. Is this irrational? Well, let’s see. When we define who a person is, do we define them by their physical characteristics, or by who they are inside? The more we know a person, the more we define them by traits that cannot be perceived with our physical senses. And so what does it mean to judge a person by their character, if not to put a premium on our subjective experiences? Or try this. Think about your experiences looking at pictures of people whom you care deeply about. Does this not give a person such tremendous pleasure? and yet even if such pleasure can be defined in terms of the scientific instruments measuring them, is that really what we define as being the most real, or rather is it the inner sense of joy we are experiencing that lies at the heart of it…again, a subjective experience?

And this reminds me of the various approaches giving evidence for G-d’s Existence. Sure we can point to the amazing physical properties of the universe, and conclude that there must be a Supreme Intelligence behind all of it, but does that truly convince those of us who are of a skeptical nature? Or we can point to the Divine revelation at Sinai experienced by our entire Jewish people, but isn’t the fact that none of us were there, at least in our current incarnations, leave some doubt in one’s mind? But then there is our spiritual yearnings…how can we have such spiritual yearnings, if we have no soul? Why do we feel spiritually uplifted when hearing music by Bach of Mozart? Why was Viktor Frankl so spot on when he pointed out how meaning in life defines us better than any other psychological theory? Again, it points to our true reality ultimately being subjective, beyond empiricism, and yet because it makes perfect sense, sure seems eminently rational to me.

Raymond,

What an amazing post. I remember reading a line from R Aryeh Kaplan that went something along the lines of “Kabbalah is an intricate field of study that answers some of the great questions that philosophy is unable to.”

If he says it, I trust him.

IMO the biggest and worst misyake that one can make with respect to these ans similar issues like theodicy is thinking that one has all the answers as opposed to an approach.

I think a better term is “intellectually honest” Judaism. History is revised, and difficult opinions are explained as forgeries. Instead of admitting that there are difficulties, we are given fatuous answers. Rabbi Slifkin’s work on the shafan and arnevet did an excellent job illustrating some if these issues. I can live with not having all the answers, just not with fake ones. We paint ourselves into intellectual corners and undermine the integrity of the mesorah.

Rabbi Adlerstein,

You know me and know that I don’t have a mystical bone in my body, except for the luz, that is.

Standing on one foot, that explains rationalism with emunah.

Cheers,

I’ve asked this question to many so-called “rationalists” and have yet to receive a satisfactory answer. When the Beis Yosef had his sessions with the magid, he was clearly delusional in the eyes of a rationalist. How could one accept the halachic rulings from someone suffering from a clear mental illness? How can one honestly believe in “rationalism” and still believe in our mesorah? Seems rather irrational.

There was a conversation that Natan Slifkin had where he was asked what he bases his beliefs on. As a frequent, somewhat critical but often in agreeement at least in principle, I was very interested in his response. I just remember that the response was very personal, not particularly rational as representative of a religious worldview, and disappointing.

What I’ve taken from his approach is that the questions are better than the answers, and that the answers leave you with an approach that might work for one personally, but is difficult to excite others about.

The bottom line is that, as dr. bill wrote, where we draw the line is important, but there are so many non-rational things within Judaism. The Exodus, Revelation, Prophecy, the afterlife, the Miracles in the Bais Hamikdosh, countless supernatural stories in the Gemara, and he list goes on.

Thank you Rabbi Adlerstein for your well reasoned remarks. As my father expressed it many years ago – “There is nothing in the Torah that is irrational, but there is much that is ‘extra-rational'”. He also visibly bristled at any reference to the Rambam as the great Rationalist.

In an age where Ignosticism seems to have won the day, we are hard pressed to focus on the Emunah P’shuta of our forebears. This is not an age of intellectual challenges, it is an age of very basic YETZER HA’RA , pervasive and all-encompassing.

Stephen Hawking left this world still searching for “the unifying principle”. His greatest accomplishment was the discovery of the Black Hole. How ironic is that?

WADR, the issue is whether the non-rationalIST Judaism is the original Judaism or something introduced later. Since we strongly oppose a certain class of innovation, shouldn’t that prohibit observance of and belief in non-rationalIST Judaism? It’s not a question of logic but of history.

(Personally, despite my questions, I continue to observe non-rationalIST Judaism.)

“Of course, no Orthodox Jew could be fully rationalist, as there is no evidence other than authority for the events of Yetzi’as Mitzrayim and Matan Torah. ”

Rational Jews tend not to have more ikkarim than are derived from basic reading of Torah.With your statement obviously dont attack OTD

” have won the day, we are hard pressed to focus on the Emunah P’shuta of our forebears.”

An emunah that within a generation of the haskalah the vast majority threwaway traditional Yahadus

That is an oversimplification. It was true in parts of Europe, and not in others. There was a mass exodus in Germany – but not in Hungary, even in the Oberland areas closer to Germany. You are correct that when Emunah Peshutah faces off against the challenges of modernity without any accompanying tools, it sometimes/often loses out. But those other tools that we more “engaged” folks pride ourselves on also fail, for want of more of the passion and commitment of the Emunah Peshutah fans.

Every generality has exceptions, but look at the percentage of Orthodox Jews in counties like Hungary, see Wikipedia article listing names of famous Hungarian Jews, famous people few if any traditional Jews. Compare number of Bundist members of Polish Parliament with those of AGUDAH. EVEN PICTURES OF PRE holocaust Eastern Europe we recalculated by spionsers to show what they believed was more exotic dress than the more modern. Look at percentage of Jews in Western Europe and North America who are Orthodox today compared to their ancestors a few centuries ago.

We apparently agree with Emunah Pshuta can’t face off against modernity by itself. The question what is likely to work to help. We need data of success twenty, thirty years after finishing HS.

The most disturbing and frightening element of Rationalist Judaism in its current gilgul is its delegitimization of financial support of Torah study. I’ve posted here previously about this issue, but as a resident of Eretz Yisrael, the words of the Netziv in his commentary to Shir HaShirim (1:8) are terrifyingly direct in their import:

שאין זכות להגין מפני אויב כי אם החזקת תורה ברבים

” How could one accept the halachic rulings from someone suffering from a clear mental illness? ”

Is the SA accepted because of its writers or was it accepted because it and the Rama reflect the practice that was generally accepted?

Was the Mishnah Berurah accepted as one of the most important guides (and for some, THE most important guide) because of the writer, or because its decisions reflected the practice that was generally accepted? Clearly the former!!!! It was the halachic greatness of the Chofetz Chaim coupled with his piety that provided the confidence in his decisions. The Aruch Ha-Shulchan certainly was a better reflection of generally accepted practice. There is no question that the perceived gadlus of a posek figures into his popularity. And so it was with both the Mechaber (revered to this day by Sefardim is “Maran,” and the Rama, who by age 16 was already famous as one of the most gifted minds of the generation

Lacosta ,

That was/is ,in all probability, a reaction to the patronizing and condescending snideness of “rationalists” for all who they deem even the slightest bit “irrational“

Because many need rationalism to get them through day as well as a better paycheck , it makes them superior?

Doron Beckerman, What does rationalist Judaism have to do with funding Torah study? I am a rationalist and most of my tzeddakah supports Torah study and Torah scholarship. Of course, i would never support any institution that supports kollel for all but the minuscule percentage of our next generation’s potential RY and poskim. That does not prove i am rational, just avoiding irrationality. Not being irrational, does not necessarily make you a rationalist.

Note as well we pasken based on halakhic sources, not machshavah, parshanut, etc.

To Gary Poretsky above:

I think “Intellectually Honest Judaism” is a far worse and much more dangerous title. We can see where it has led Rabbi Slifkin in the very area you praise him fo. He felt compelled to conclude that the shafan of the Torah is not in fact maaleh geirah even though the Torah says it is because he refused to be painted into an intellectual corner regarding the truth of the Torah’s claims about the physical realtiy.

It would seem his brand of intellectual honesty indeed leads one to undermine the integrity of our mesorah.

The key is as Mycroft indicated whether Torah Avodah and Gmilus Chasadim the three elements emphasized bu Shimon HaTzaduk are successfuly transmitted to the next generation. Go to lots of simchas and you can detect the success or lack thereof as to each elememt. Hashkafa supplements but never should be seen as supplantinng those three elements regardless of where you are on the self defined hashkafic spectrum. No less than R Velvel.Zl attributed his success with his sons to a lot of Tefilos and Tehilim.

Perhaps we need to realize that neither a purely rational nor an Emunah Pshuta approach but rather elements of both will appeal to different people. The Chasid Yaavetz wrote that those in Spain who lived by Emunah Pshuta as opposed to pure rationalists did not assimilate at the time of the Spanish Explusion. Whether munah Psshuta has validity depends IMO on the degree of validation one gives to the culture of the secular world today. We are not faced today with the ideological challenges that confronted the Western and Eastern European communities such as Hasklala Reform secular Zionism and the many varieties of socialism. We are confronted with a different ideology-that we can do whatever we want whenever we want to based on our decision that the same makes sense today and is rational, regardless of cogent and powerful arguments to the contrary. Any ideology or way of life that threatens to supplant Torah Avodah and Gmilus Chasadim and supplant it in order to meet the Zeitgesit of the time whether as a threat to free exercise of religion in a blatant or not so blatant way, culturally ,socially,politically, and especially is a threat to the conventional Jewish family has to be confronted when necessary in an intellectually honest and cogent way.

Of course we will be distracted by the use of labels to define the nature of our beliefs. Rationalist cannot possibly mean that we have a deep penetrating understanding of the essentials of faith. This would be impossible, since much of what we have internalized as part of our belief structure is no really subject to being understood, or even visualized. However what one means when he says rationalist is that we should apply what we believe and what we have been taught to our lives in a rational way.

For example, we may not understand everything about kashrus, or tznius, of even frumkeit . But we can still say that in our lives we have to approach what happens t us in a logical way, and do what makes sense.

To me this means that we should recognize that we are responsible for our decisions, and we should not avoid responsibility by allowing other people or other modes of thinking to make decisions for us. To many of us accept what we are not sure about because we are expected to. This is neither rational nor rationalist

Rabbi Adlerstein, i am happy you added “perceived” to modify gadlus. Important poskim of the previous generation did not all accord the MB priority over the OH that covered all 4 chelkai SA and the SA haAtid. Your binary choice (the perceived stature versus conformance to practice) does not come close to exhausting the relative factors, as I (would have) assumed you are aware.

There are chumrot in the MB that make the CS and the CI early adopters of OO. 🙂

In my youth, the MB was unheard of my circles. The AH was the standard for western european Orthodoxy. We turned off lights on Yom Tov, heaven forfend! Many still follow AH, including this MB. Think about milk and meat ovens!

MB, said in a slightly different context about microphones by the Rav ztl, the osrim do not understand physics, the matirim don’t understand halakha.

in a well-known story from the forties which I heard from an eye-witness who has since died, on instruction from RCH ztl, his adopted father-figure, he answered the phone on YT when instructed by his rebbe to do so. it involved a case of possible safek nephashot.

we have become machmirim wrt electricity, something advances in various areas will require poskim to re-evaluate. medical, security, etc. issues even involving less than absolutely life-threatening situations will force a reevaluation. in reality, new forms of electronics raise entirely new issues that poskim have not always analyzed completely. unfortunately, i have seen pashkevalim attacking what was paskened leniently by both RSZA ztl and RMF ztl. sad but true.

Rationalism and rationality, wrote Deirdre McCloskey, “are not often found in the same company.*” People who claim to be rationalists are often not wholly rational.

examples: ego-involvement. The moment we’ve expressed a view, we feel we own it and have to defend it: this is a form of the endowment effect. We thus look for confirmatory evidence and downplay dissonant evidence. The more public your writings, or the more tied up your ideas are with your sense of identity, the greater these dangers will be

What’s more, like Michael Oakeshott, I’m not sure that rationalism (at least in some senses) is appropriate for human affairs. We cannot treat these as mere operations of logic in part simply because there are too many plausible premises to start from. Niels Bohr’s saying fits the social sciences well: the opposite of a great truth is another great truth; I find that the appropriate response to very many claims is “yes, but.” The crooked timber of humanity does not fit logical schema.

Instead, our thinking should be a movement

What matters, is not so much that one be rational as reasonable