THE PLACE FROM AFAR: A Tale of Three Sisters

דּ וַיִּשָּׂ֨א אַבְרָהָ֧ם אֶת־עֵינָ֛יו וַיַּ֥רְא אֶת־הַמָּק֖וֹם מֵֽרָחֹֽק:

And Avraham lifted his eyes, and saw the place from afar.

Every year on the 4th of July, Candis made me a birthday party.

She must have been nine and I six when the tradition began. She’d send “You’re Invited!” cards to all the girls in my class at school, and on the appointed day, would set up the picnic table out on our front lawn, with party favors and party hats, and red, white, and blue balloons. She’d organize party games and contests, and judiciously distribute prizes. And although ever since her younger sister had come about, Candis had less access to her mother’s arms, and lap…and less of a share, in general, of childhood’s bounty…she would stand me up on a chair and clap when I blew out the candles, and she and Mommy would lead everyone in singing “Happy Birthday to You!”

Most importantly, (after several years of our mother’s homemade “ice cream,” made with eggs from her organically-raised hens in the chicken coop out in back of the house; and the homemade birthday cakes which were so nutritious, we could have had them for lunch, with their questionable “icing” made of raw honey and carob powder) it was Candis who succeeded in persuading Mommy to get ice cream from the supermarket for Sarah’s parties, and a real birthday cake from the Swiss Chalet, with artificial food coloring.

No small achievement. For Mommy took personal responsibility for the health of anyone–as she’d sometimes say–“who walks through our front door.” And through the years there were hundreds of guests who entered our family’s life. She was as adamant about serving a balanced meal (with at least two vegetables from her organic garden) to the people she hired to help her around the house as she was to any politician, diplomat, or literary star who came our way…whether the guest in question had survived the Nazis or the Atomic Bomb…or hailed from Africa or India, Egypt or France, or any other country….whether he or she was one of our Yiddish-speaking relatives from Long Island, or a child from next door.

In honor of Independence Day, Daddy would have written an editorial for his magazine about the noble humanitarian ideals of American democracy and the nation’s Founding Fathers, and after dinner he would take us to the annual 4th of July fireworks, where along with hundreds of other suburban families, we’d stand in the dark and behold with awe the magnificent starry explosions celebrating America’s birth and mine.

My happiness was America’s happiness. Our birthdays intertwined.

I loved the day we were born.

*****

Upon entering Andrea’s living room when I arrived from Boston Airport, the sight of her on the couch blew a fuse in my heart. I struggled to control my face.

Andrea–she who had always been the beauty of the family–the brilliant, the articulate, the accomplished psychoanalyst…she who’d been elegant and petite was now emaciated, and too weak to rise. She lifted her head from the pillow slightly, and with a broad, warm smile, reached out to me in welcome, the sleeve of her nightgown slipping down along a bone-thin arm.

“It’s hard to find things that she’ll eat,” Candis informed me in a whisper later that night in the kitchen, giving me a heads-up about all the fast-moving developments since I’d been with Andrea a few months before. “The doctor at Beth Israel said that at this point, nutrition doesn’t matter. We should just give her what she wants.”

“So what does she want?”

“She’ll eat a little ice cream. She doesn’t ask for it, but she’ll have it if I give it to her in one of the very small cups. Only vanilla. And she likes white toast with butter.”

“Not whole wheat?”

“No. Just white.” Candis smiled wryly. “It’s more exciting.”

*****

Still on Israel time, I awoke from uneasy dreams and looked on from under the covers as the cold darkness outside Andrea’s guestroom windows yielded slowly to dawn.

In the night, an early-season snow had fallen, settling lightly down over the brown-green ground.

I was glad. I’d been hoping it would snow while Candis and I were here. Andrea’s illness had brought us together, and there was snow, somehow, in that picture: the two of us venturing out into our shared childhood…the long-ago playground. If we could just take a walk in the snow together, maybe we‘d talk…and heal the rift.

Gnarled old trees huddling along the low stone wall, on the border of Andrea’s property. Trees in the distance, climbing the flank of Bear Mountain. Younger , smaller trees here and there, amid dry, overgrown winter grass.

And at the other end of the meadow, long thin trees were lifting their limbs into an opaque sky–a delicate, lacey filagree of intertwining black branches, each branch lined with white.

Trees, trees, and trees beyond trees.

I knew this beauty; it’s imprinted in my brain. We grew up with it in Connecticut. It’s the New England landscape I’d known my whole life, and whose beauty my heart loves.

I recognized intellectually that the beauty couldn’t be any less beautiful now than it had ever been. But there was a veil, somehow, between it and me.

I shut my eyes.

In the dark behind my closed lids, there were the placards on sticks that I’d caught sight at the entrance to Andrea’s driveway: a cluster of signs planted in the ground next to a line of neighbors’ mailboxes: “From the River to the Sea.” “Resistance by Any Means!” “Free Palestine!” “Resistance Is Not Terrorism.”

The trees didn’t feel like my trees anymore.

***

Andrea had chosen many years ago (less for its own sake than for the land that came with it) to live in an isolated log house, away from the road. She held the world of Nature and its animal inhabitants sacred, and in this area of Massachusetts, the “natural world” is

probably more revered and protected than anywhere else in the USA. Environmental legislation mandates recycling. Chemical fertilizer’s a thing of the past. Organizations arrange adoption for orphaned or abandoned animals. Animals, in general, are legally entitled to levels of care, housing, and medical attention that could easily rival anything accorded human children (and young children, in any case, are not found in great numbers in this social milieu.)

When the Uber I’d taken from the airport turned off the Interstate and onto the winding two-lane road that continues through the miles upon miles of woodland on the way to Andrea’s home, my gaze took in—as usual whenever I’ve traveled there–all the classic Colonial houses presiding amidst the trees. In this neck of the woods, no one house is identical to any other, and each is lovelier than the one before. (I couldn’t help but notice my relief upon catching sight of an ugly 1950s-style split-level, its pickup truck parked out in front.) These Early American homes, artfully redone in subtle contemporary color schemes –pale pink, ivy green, dark brown, sky blue, lemon yellow, charcoal black…with window frames painted turquoise or deep rose or maroon…and front doors crowned by the hand-crafted antique wooden signs that boast of their Civil War vintage, dates such as 1799 or 1860, and a few from the 1600s, attesting to their Pilgrim pedigree.

Elegantly renovated, set amidst well-maintained gardens and lawns, these homes blend imagery of the American pioneer spirit with state-of-the-art modernity and comfort, and eloquently proclaim the sophisticated tastes and creativity of the discerning, upright Americans dwelling within.

Not to mention the graceful simplicity and modest self-presentation of all the white wooden churches dotting the landscape here, there, and everywhere, many of which date back to America’s founding. How reminiscent they are of the Congregational Church in my hometown…and of the deep self-doubt it aroused in the heart of an assimilated Jewish child.

To be subjected to all these beautiful houses, one after the other, has always given my covetous yetzer hara a run for its money. And as usual, it was with a guilty sense of disloyalty to Eretz Yisrael that I found myself comparing this scenery to the one tree outside our living room window in Jerusalem, and the one-size-fits-all residential high-rise buildings sprouting up all over the Promised Land, where apartments are small and families large.

It’s the ingathering of the exiles, I corrected myself sternly. Say “Thank You, G-d!”

***

Some of the friends who came to my birthday parties–-our heads crowned now with white—still remember that July 4th is Sarah Cousins’ birthday (though I don’t remember theirs). The number attached to the occasion gets constantly higher and less plausible every year, and pertains as much to them as to me, so we skip that part.

And when the class in its entirety has its annual reunions, held nowadays online, we engage in determinedly casual conversation. We don’t discuss the paths we’ve taken, or speak of what we’ve lost, or question the purpose of our sojourn in this world.

Who am I? We skip that part.

Who are you? Life is a breeze, with some knee and hip replacements, and bypasses.

To the classmate who moved after high school into the foreign turbulence of the Middle East, they offer their prayers for peace in the region and urge me to “please stay safe.” Both they and I refrain, no less than we ever did in the 1950s and ‘60s, from mentioning the curiously radioactive 3-letter word which in spite of my secular family’s assimilation, had mutely referred—in my mind, if not in theirs–to the unspoken distinction that set me apart.

As a little girl I identified gloomily, wishing I didn’t have to, with the people in We Have Not Forgotten–a large coffee-table-sized book of black-and-white photographs. I’d come across it while playing in our attic storeroom, and in its pages encountered compliant, wretched people who in some pictures were lined up along the edge of deep pits for their own burial, said the book, which they themselves had dug, In other pictures, they looked out at me, dead-eyed and skeletal, from behind barbed wire…people who for reasons no one was telling me, had been elected for punishment, trapped and murdered in the decade before I was born. I was ashamed. A decade, though, seemed to me a very long time, and those people of the 1940s had inhabited a history far removed from America—removed not only by time but by virtue of that era’s total strangeness and horror.

It was with nary a backward glance that as a teenager I left my hometown for good, and the children with whom I had traveled from one grade to the next, 1st grade to 12th. I was non-plussed to be leaving the children who had served as the props and landmarks of my childhood drama. Only with the passage of time have I sensed the depth of their roots in my psyche, as inextricably planted in the soil of my heart as if we’d been 1st cousins.

When our 2023 class reunion on Zoom came about not long after the Hamas Massacre on October 7th, my best friend in 2nd grade expressed her hope that I and my fellow Israelis would prevail “in your ancestral homeland.” But Israel, she said gently, shouldn’t engage “in a futile cycle of violence. War is never the answer. It really upsets me when people can’t get along.”

Upon hearing those placid words of advice, a surge of speechless, impatient fury blasted through my heart, and I thought mistakenly that I’d never attend another reunion.

|

Another friend reminded those of us in attendance that Sarah’s father had been a leading advocate for the United Nations, and a pivotal national figure in the 1960s and 70s for the cause of world peace through world government. “Yes,” said I. “I know.” Indeed, a belief in the potential for good that exists equally in every human being, was bequeathed to me in my bones by my mother and father both. ***

|

Until our grandmother, Sarah a”h, died and Candis, age 12, was given the room downstairs that Mom had occupied, the two of us shared a small yellow bedroom up in the attic, under the slanting slate roof of our big old house.

A tall maple’s uppermost limbs leaned in, green and full, at the arched dormer window, and in winter, all the black branches would be lined with snow.

At bedtime, after our mother would kiss us goodnight and turn out the light, we’d await the sound of her hurrying footsteps on the stairs.

Then the show would begin.

I can still see in my mind’s eye Candis’s shadowy little figure atop the twin bed next to mine, putting on one of her comic pantomimes in the dark. Sometimes I’d laugh so hard that in a reflex neither of us could fathom, I’d start to cry, and catching my breath between laughter and sobs, I’d beg, “Stop it, Candis! Stop it!”

Candis’s move to a room of her own was my introduction to one of life’s essential, inevitable, and most important emotions: loneliness—cradle of many sorrows—that served as the void from which I had to emerge, like a chick from its breaking shell. It’s the emptiness that prompts human beings to lift up our eyes.

In the wake of her departure, I set about scotch-taping dozens of Museum of Modern Art postcards all over the yellow walls, mistakenly imagining that Impressionist paintings by Degas and Monet and Van Gogh would make me sophisticated and interesting in my big sisters’ eyes, and entice them to come upstairs and play.

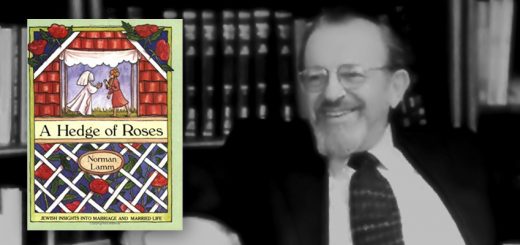

The summer of my 14th year, our parents brought Candis and me with them to what back then was called the Soviet Union. Our father, the writer and magazine editor Norman Cousins zt”l, known today as the man who used the power of laughter for recovery from illness, was leading a 2-week conference for Russian and American writers, artists, and scientists. The conference’s goal was to influence both countries’ governments to achieve global nuclear disarmament.

Candis and I had a blast in Russia, exploring Leningrad and Moscow on foot together, auditing the conference, writing notes back and forth when we’d get bored, meeting the famous people in attendance such as the writer John Kenneth Galbraith, and the geodesic dome inventor, Buckminster Fuller. There’d been warnings that overhead light fixtures in the Americans’ hotel rooms were probably bugged by the Soviet Secret Service, so before going to sleep at night, Candis and I would address ourselves cordially to the crystal chandelier and give friendly speeches about world peace to Premier Nikita Khruschev.

Moments after our plane departed from Moscow, the above-mentioned life-threatening illness burst forth, and subsequent blood tests in the hospital determined that my father had been poisoned. Though it was President John F. Kennedy who had dispatched him as the U.S. emissary in the movement for nuclear disarmament, the Russian and American militaries did not look fondly upon such efforts, and the Soviet KGB, apparently, chose to be proactive in their traditional manner.

My father survived, as did his idealism. He had often said, “No one gets out of this world alive,” and the attempt on his life (which for the sake of US-Soviet relations, he didn’t make public) did not alter his general modus operandi: relate to the good in a person and you will find it.

Upon our return home, Candis took off for her freshman year at college and I entered my freshman year of high school. How I wished she were at home! I wished she were still in high school–the popular, vivacious, socially at ease. academically accomplished sister whose presence, I thought, would have boosted my social standing and self-confidence. I was crushed by her absence and missed her so badly that twice a year for the next four years, during the spring and winter breaks, I went by train to Ohio and stayed with her in her dorm. She received me with open arms, granting me entrée into her new world.

At Oberlin. Candis was taking a course in Jewish History. Well, without such description ever having been articulated, she had always been thought of in our family as “the Jewish one.” For only she, of the daughters, manifested any inclination, in our Anglo-Saxon Protestant suburb, to explore our immigrant grandparents’ religion.

***

Candis and I had been disagreeing for years about Israel and the Palestinians. But in the wake of the October 7th Massacre, our long-distance conversations, no matter how they began, would end invariably on a furious, bitterly personal note. Candis broke down and wept on one occasion when telling me about the horrific suffering of Palestinian women and children in Gaza, and her pain on the Palestinian people’s behalf at one point caused her to suffer severe abdominal spasms and shortness of breath. “I have come to realize,” she told me one night during a conversation on Zoom , “that I bear responsibility for this war because America provides Israel with its bombs,” whereupon I lashed out: “Aren’t you aware of Hamas’s use of human shields? Hamas builds its military infrastructure underneath their own people’s residential buildings and hospitals and schools so that naïve Americans—like you!–who have no idea what‘s actually going on, and don’t know what you’re talking about!—will be able to hold Israel solely responsible for the Palestinians’ suffering!”

One or the other of us would get back in touch afterwards to apologize. Time after time, we would be relieved to hear that the other one had lost sleep over our argument, too, and regretted it as much as one had oneself, and was equally depressed and frightened by what we were doing to ourselves.

I’d seen it written somewhere that Jews should not argue with one another about Israel, because such arguments are always about the branches instead of the roots. But our fights continued. Our inability to talk respectfully with each other when it came to Israel had caused an undeniable chasm to open up between us.

We resolved more than once, and more than twice, to simply not talk to each other about Israel and the war. Our relationship was too central in our lives for both of us. What was becoming apparent, however, was that our relationship to Israel was also primal, and also at the center of our psyches. So the effect of our not talking about the elephant in the room was that in each other’s presence we were emptied out of whatever it is that makes both of us tick. We’d converse carefully–two hollowed shells—skimming politely around ourselves.

We finally just stopped talking.

Weeks went by.

Then Candis got back in touch. She had an idea, she said: Why not ask my son Yehuda, whose work involves facilitating connections between non-observant and observant Jews, to moderate our conversations.

She elaborated in a subsequent email:

Mon, Jul 22,

Dearest One,

I wish Daddy were here so you, Yehuda, Daddy, and I could talk about what’s happening on the West Bank and Gaza.

Neither you nor I are in Gaza or in the West Bank.

Here are my sources of information

- Interviews on British Broadcasting Network, American public TV and radio with people who live in Gaza and the West Bank, doctors and humanitarian aid workers who have been or who are now there— people who are the children and spouses of doctors and nurses and reporters who have been killed; family members who have lost children, mothers and fathers. (I do not get my news from commercially sponsored media.)

- Film footage of what Gaza looks like from the above sources — the bombed cities, hospitals, schools, whole cities destroyed, aid trucks which have been bombed, children who have lost mothers, fathers, sisters, baby brothers and sisters, children who have lost limbs, children who are starving.

- New York Times (rigorous fact checking)

- Haaretz (Respected by the editor of the New Yorker), especially Amos Herel . (Our friend Stan who was a writer for the Wall Street Journal, the New Yorker, and was a professor of Journalism at University of California, Berkeley, says that Haaretz is the most respected newspaper by the international journalism community.

- International Rescue Committee

- International Court of Justice

- Amnesty International

- The New Yorker (rigorous fact-checking )

- The Telegraph (UK)

Please tell me what your sources are so I can read what you are reading. Since you like to speak with Israeli Arab cab drivers, could you ask them the following questions: “Have you lost any family or close friends in Gaza or the West Bank? How did they die? What do Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank tell you about what their lives are like? ” Would you like to read Daddy’s book together, The Pathology of Power?

Sarah, you know far more than I do about what it’s like to look up and see rockets in the sky.

I have never experienced that fear. You know far more than I what your friends and family are experiencing in the observant community in Jerusalem.

Perhaps, writing back and forth might be a better way than speaking in person.

With love,

Candis

***

|

|

My sources, Cand? Yeah, I’ve got a few. (Does living here count?)

Off the top of my head:

It’s 1983. Home is a 2-room trailer on Maalei Amos, a yishuv in the Judean Desert that has been established by Rabbi Noach Weinberg, zt”l. for his yeshiva’s thirty kollel families. My children–four under the age of four—are jumping wildly up and down on a couch and waving and yelling, “Shalom! Shalom!” through our open living room window.

One of five identical so-called “caravans” lined up in a row along the settlement’s sandy outer edge, the living room looks out onto the narrow, one-lane country road that ran parallel to the settlement. Why are the children so happy and excited? Because as he does every day–in the morning heading east and in evenings, west–a thin little Palestinian child, around ten, from the nearby village, leads a little grey donkey by a rope, and riding bareback on the animal are a little boy and a little girl, around the same size and age as my four-year-old twins.

Moved by my children’s openheartedness, I stand behind them, my heart stirred by pride and optimism. I am successfully inculcating, as my parents had in me, the ideal of respect and love for one’s fellow man. I’m a believer, and G-d willing, my children will be, too.

With goodwill and good individuals on both sides, I know that peace is possible.

Next: a photographic image from the year 2000.

A man stands at an open window in the city of Ramallah, triumphantly lifting two arms aloft in a gesture of exultation. The palms of his hands, and his shirt and forearms, are red with blood, and before him, an ululating crowd of Palestinian Arabs is celebrating with him the lynching of two Israeli reserve soldiers who had taken a wrong turn into their Palestinian city.

The man at the window (I’ve decided not to include the lynching’s horrifying details) was arrested by Israel in 2001, sentenced to life imprisonment, and was subsequently released in the 2011 exchange of one Israeli hostage for 1,027 Palestinians prisoners (among whom was the Hamas leader, Yahya Sinwar, chief orchestrator of the October 7th Massacre,)

At that point in time, I had lived in Israel already for 25 years, and was thus familiar with the phenomenon of Islamic jihad. The event was not unusual. Yet for some reason, it was that particular picture which in a fraction of a second extinguished.my lifelong innocence.

It cut the umbilical cord to my family inheritance.

I have hope that my innocence will be restored in time to come.

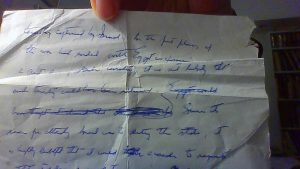

My third offering: an undated stray page from a spiral notebook, with notes on it in my father’s handwriting. I came across the page among my own papers some years after his death.

He must have been composing his weekly Saturday Review editorial. Incomplete without the other pages, which presumably were thrown away after he typed up his notes, the part that’s there reads as follows:

territory captured by Israel. In the first place, if the war had ended with Egypt in possession of a great deal of Israeli territory, it is not likely that such territory would have been returned. Since its reason for attacking Israel was to destroy the state, it is highly doubtful that it would agree to requests that it relinquish any of its war gains. In that light, it is not reasonable to expect Israel to give up everything it gained during a war which could have resulted in its own extinction. But this notion of phased returns of territory over a period of time, tied to the consolidation of Israel’s security requirements, would certainly meet Sadat’s need to show that he could crack the Israeli desire to hold on to everything for all time. For his part,

That’s as far as it goes.

I. too, wish that Candis and Yehuda and I could sit together with our sensitive, compassionate, deeply rational forebear.

***

Andrea and I were talking. She was on the couch, I in her rocking chair, when she said, “I don’t know what to do.”

“About what?”

“About what?”

“You said you don’t know what to do.”

“I don’t want to die.” She turned her head slightly on the pillow to look at me. “I’m scared of dying.” She waited. “Aren’t you?”

I hesitated. “Of other people’s deaths, yes. I’m very scared of losing people I love. But I don’t think I’m scared of dying myself. And I think that’s because I know that we don’t die when the body dies.”

“I don’t believe that.”

“We can’t conceive of it because we’re in our physical selves.”

“If you’re not scared, it’s because you’re not facing it.

“In Israel, we face it.”

“No. you don’t. It’s still an abstraction. For me, I know I’m going to die. Soon.”

She closed her eyes.

***

We did go for a walk in the snow, Candis and I. She took my arm and out we went, into the woods. She showed me where beavers had once built a dam, and explained how because of the dam, a big, beautiful stream had developed there. “It’s not there now, but it was beautiful. That’s what beaver dams do. They create bodies of water. It’s amazing.”

We talked about many things.

“You were always the Jewish one in the family,” I said at one point.

“You know why? Because of Alex Naftalin.”

“Really? I remember Alex!”

“We were friends for 10 years, from third grade on. Her father was an Orthodox rabbi in Stamford and I used to go there for Shabbos”

“Every week?

“No, not every week, but I loved it.”

“Did Mommy and Daddy know?”

“Yes. But they didn’t understand. Sarah…” Candis turned her head to me and looked me in the eye. “Just think what it would have been like, if Mommy and Daddy had known about Shabbos. That one thing would have made such a big difference.”

The snow under our shoes was melting. “Candis, thank you for making me birthday parties. You made me aware of myself as a person . You made me feel important. You gave me recognition.”

“And now,” she said. “you’re giving me recognition. And making me feel important.”

***

Last night, talking on the phone 9 months later—Candis at home in Oakland in the morning light, looking out her studio window onto their rock garden below, and I in Jerusalem, looking out at dusk through our living room window into the tree next to our building–the tree that single-handedly manifests for us winter, spring, summer and fall. Its branches are full of the green-brown leaves of autumn in the Middle East.

We’re trying to recall if we took that walk in the snow before Andrea died or after.

“Well, when she was still alive, we couldn’t have both gone out at the same time,” said Candis. “One of us would have stayed with her.”

“Right. And we wouldn’t have left when her body was in the living room. So it must’ve been after they carried her out.”

“Remember the way you cried, Sarah? When they carried her out? It was one long, long scream. Remember?”

“Yes. I remember”

“I think that’s when you realized she had died.”

“Yes.”

We talked about other things and were about to say goodbye when I said. “Candis, you know there’s a quote that I read by a 20th century rabbi–I don’t remember who. He said that it’s not worthwhile for Jews to argue with one another about Eretz Israel, that arguments about Israel will not bear fruit, because the arguments are always about the branches instead of the roots,”

We fell comfortably silent for a few moments. Then Candis said, “Do you remember when we used to talk in the dark when we shared the room up on top of the house, how we used to talk about colors?”

“Colors?”

“Yes. We’d take turns making up names for colors, and imagining them in the dark. I’d say something like ‘Cinnamon brown,’ and then you’d say something like ‘Bubblegum Pink.’ Or ‘Spring green.’”

All of a sudden, something stirred underground—a lovely, weightless thing, like a leaf, fluttering lightly upwards all at once through the years. “Burnt orange!”

“Yes!” she exclaimed. “Burnt orange!”

We laughed in triumph.

L’iluy neshama Nachum ben Shmuel

L’iluy neshama Andrea bas Nachum

[This article first appeared in AMI]

In all honesty, I can well appreciate the desire to see one’s parents in a positive light, or at the very least to show kibbud av. So I will try to be respectful. But: The Soviet Union was evil. This was not a secret even in the 1960’s. It repressed its own people, murdering them in the tens of millions, and let’s not even start on what it did to Jews and Judaism. It also aimed to take over the world and do the same to the rest of the planet, and one of its most notorious fronts in doing so was its “peace” efforts; another, of course, was the physical and propaganda attack on Israel.

That someone could be *poisoned* by the regime and consciously cover it up for “the greater good” may be seen as complete self-abnegation, which can be a sign of a moral hero, but not if it is in defense of a evil empire. Which leaves certain questions.

But to the point: Is it all possible that seventy years of the intellectual classes of the West ignoring all this, and preaching moral equivalence (or worse) of Communism, may have contributed, just a bit, to the constant attacks we see on Israel and Jews among the fashionable classes and academics of today? To ask is to answer.

The purpose of Norman Cousins’s negotiations with Russia on behalf of President Kennedy in the early 1960s was to prevent a nuclear exchange in the wake of the Cuban Missile Crisis. The negotiations had nothing to do, as “Nachum” theorizes in his comment, with any sort of “moral equivalence” drawn between Communism and democracy. nor was it indicative of any condoning of evil.

That my father zt”l refrained from going public about the attempt on his life was not done “in defense of an evil empire,” as “Nachum”—lacking any historical information about the events in question– speculates irresponsibly in an anonymous post. On the contrary, as noted in the story, Norman Cousins held his tongue in order to keep international negotiations on track, even though he himself was too ill to continue.

He did indeed act for “the greater good.”

One needn’t be a daughter to view such deeds “in a positive light.”

Nachum is my real name and I attach an actual email address to my posts, in which my last name is clear.

Would you be able to share, then, your father’s views- and yours- of the USSR? Did he ever discuss the treatment of Jews? This became a huge issue in the late 60’s and early 70’s. What were his views as it began to collapse in the 1980’s?

A personal Tefilah -that the author and her sister maintain their relationship despite their differences and views

Amen.

Hi Sarah, I love your writing your openness and your honesty, the beauty of the words you use to draw imagery and relationships in our minds. The subject you represent is so important, so painful. Thank G-d you realize good and evil but not all of us, even our own family can. The lost innocence you describe is painted so profoundly by you and Bari Weiss along with thousands of liberal Jews worldwide choosing between betraying their people & their homeland or their indonctrinated values family and friends. Keeping the dialogue open despite the hardships allows the pheonix of relationships to rise above the pain of ignorance. Hopefully the uncomfortable silence and or traitorous behaivior of our fellow Jews and Non- Jewish “friends” will allow more Jews to make Aliya in droves. Any leaders or groups interested in information from regular people about which location is best for them to move to in Israel can contact [email protected]

Given the political views of Norman Cousins, his daughter’s political views are actually understandable. 85% of Americans supported dropping the atom bomb. It was estimated that failure to do so would cost a million lives in prolonged combat due to the Japanese use of Kamikaze pilots . Norman Cousins however was an outspoken opponent who stated that he felt “the deepest guilt” over the bomb’s use on human beings.

For most of today’s young (and older) secular Jews their hostility towards Israel stems from that they’re desperate to assimilate. The highest form of assimilation is to assimilate to those who want to annihilate the Jews. The best way to show gentiles that you’re not a “tribal Jew” is to become an anti-Jew. Someone who grew up in a house that consistently took the far left view about all conflicts, whether it was poplar in non-Jewish society to do so or not, probably does not have those motivations.

May Andrea get well and along with all secular Jews return to following the Torah.