Holocaust History Comes Home

Reaching out and touching the one of the crematoria doors in Auschwitz-Birkenau a few weeks ago was emotionally jarring. Visiting my mother’s home town of Konstanz, Germany, made it personal. My youngest son and I walked the streets that she did on the way to the schools that still stood. We paused at the apartment from which she and her mother were given a few minutes to pack one suitcase, and taken to a collection point to board a train for a journey of over two days to a concentration camp in southern Vichy France near the Pyrenees and the border with Spain. Awaiting them there were bare barracks, used to house refugee soldiers from the Spanish civil war. There was no plumbing, and there were no beds. Nor was there any pavement, while an almost daily rainfall kept the ground maintained as perpetual thick mud. Many died at Gurs, but it was better than what awaited the rest at Auschwitz, which is where most wound up in 1942. The exceptions were those like my mother, whose paperwork for leaving for the US was already in progress. They were allowed to leave in the earlier days of the war. My mother was among the very last Jews allowed out of the camp.

It came as a surprise to me that the roundup in Konstanz came as a surprise to its Jews – especially those who did not really identify as Jews, and did not participate in anything together with the Jewish community. Couldn’t they see it coming as soon as Hitler took power? Well, no, it was explained to me. Sure, they thought, Hitler had it in for Jews, but it was only the obvious Jews – the Eastern European ones who looked so Jewish, whose appearance so sickened Hitler – that he was likely to go after, they thought. Just like their descendants in America would think some eighty years later as visible Jews in Brooklyn began to be assaulted in the streets.

We visited the site at which stood the large shul that was so solidly built, that it took the Nazis three attempts to destroy it on Kristallnacht. It wouldn’t catch fire, because the flammable material had already disappeared three years earlier, when unknown individuals set fire to the shul, destroying six sifrei Torah. At that time, the fire brigade came out to control the fire, and the shul reopened. The city fathers, however, never found – or tried to find – the responsible parties. On the night of the national pogrom, the Nazis also called in the fire department, this time to efficiently set fire to the building by dousing it with a flammable oil. When that didn’t work, they sent for reinforcements from an SS training facility a few kilometers away. They found a “final solution” to the problematic shul. They dynamited it.

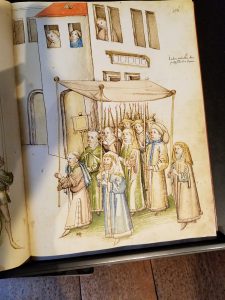

Prior to my visit, I had a vague sense that my family on my mother’s side had lived in Germany for some six hundred years. I had thought of those centuries as Jews living simple lives in organized communities in mostly rural settings, paying exorbitant taxes, but otherwise flying under the radar, their lives punctuated by occasional episodes of great tragedy like pogroms, Crusades, and blood libels. In Konstanz, it was a bit more complex. Jews actually disappeared for four centuries. In the middle of the 15th century, Konstanz, which have become an important mercantile center on the Rhine, became the site of an extended Church meeting, the Council of Constance, between 1414-1418. It succeeded in dislodging two out of three claimants to the papal throne. The town archives include a chronicle of events in the city going back centuries, including period illustrations. One of them shows a delegation of Jews presenting themselves to the pope. None of them appeared particularly unhappy, including some of the Jews in the back who were wearing the yellow caps that Jews were obligated to wear. Apparently, they asked the pope for some limited civil rights, and for a guarantee of protection. (They needed it. By this time, hundereds had previously lost their lives in one of the usual host desecration charges, and in a Black Death frenzy.) Their presence in the city was considered economically advantageous; Pope MartinV granted their request, which was honored by King Sigismund as well.

That was good for the Jews, right? Maybe not. During those years, drawn by the council presence and an expanding economy, many people descended on the city in large gatherings, running up large bills at lodges and taverns. Often they would skip town without paying. The aggrieved hospitality providers complained to the pope, who came up with a simple, elegant, and brilliant solution. “Let the Jews pay!” (Did you really think that only Jews could be so clever?) Moreover, the Konstanz Jews had previously been extorted to build a tower fortress for the wall of the city. This made it easier to round up the men, and incarcerate them in the Jews’ Tower until they were ransomed. (Ever mindful of the requirements of both tzniyus and of egalitarianism, the women were held in a different location.)

In any event, the period of enhanced rights did not last very long. By 1432, some pretext got the residents really upset about the Jews, and they were officially expelled, although the authorities were not so efficient about it till a second expulsion order a century later.

Konstanz then went a long time without Jews. Four centuries, to be exact, from the original expulsion order, till the very end of the nineteenth century. The Baden region of the country was progressive, and it offered civil rights to all – even Jews. This once again was good for the city, as successful merchants brought in quality goods, and professionals brought not only their skills, but financed new construction in what had been a medieval city.

Those civil rights culminated, of course, in their deportation during the Holocaust, which demonstrates that you can’t win, at least if you were Jewish in Europe.

Petra, our guide to Konstanz was remarkable. Trained as a biologist, she works in the sociology department of the local university. She is married, and the mother of four. As a young student, she read about the Holocaust, and became committed to see that the memory of Konstanz Jewry, particularly the Jews taken by the Nazi death machine, would not be forgotten. She got involved with the Stolpersteine project to commemorate those who were taken by the Nazis by fixing brass plaques in the pavement in their last place of residence. She works with volunteer students in a local high school (the one my mother attended, before all Jews were ejected) to care for them, and to tell their stories at an annual Kristallnacht commemoration.

In the evening, I spoke about Christian roots of anti-Semitism, and positive developments after the Holocaust. The crowd was almost entirely Christian, but they received the lecture extremely warmly, despite the fact that I was pretty strong and direct about the grossly unbalanced approach that mainline churches (the ones they were all members of) took towards Israel, and how that betrayed a simmering, implicit rejection of Jews. During the Q&A, one person rose to give a speech (doing that during Q&A sessions apparently happens on both sides of the Atlantic) about how guilty Christians were for mistreatment of Jews, and how they had to change things. From the same local high school came some students, a history teacher who designed a curriculum on religious tolerance and who teaches about the Holocaust (including taking students on a school trip to visit the Gurs concentration camp), and a parent leader. The latter was a Muslim woman from Turkey, who was enthusiastic about the need to educate children about the horrors of the Holocaust.

I can’t say that meeting a sizable number of good, decent people was sufficient to dispel the gloom and miasma of the previous hours. But it did put a dent into it. Will those people reverse or slow down the perpetuation of centuries of deep-seated and pervasive anti-Semitism in Europe? I can’t be optimistic. But it might function in a different, important way. It helps us be mindful of the exceptions – of the capacity for all kinds of people to be genuinely good. It is a reminder that the tzekem Elokim / the image of G-d functions well in many people, giving us something to both respect and to work with.

great article

In comparing Europe with America, my overwhelming impression is that it is as if Europeans cannot help but hate us Jews, that somehow such hatred is in their genes, or at least is the default position, whereas here in America, it is the very opposite of that. I am not sure why this is, but perhaps it may have something to do with America being founded and developed essentially by Puritans and their ideological descendants, the Evangelical Christians. The whole purpose of the Puritan movement was to continue Martin Luther’s call to return Christianity back to its Old Testament roots. All this is one of the great ironies of history, since Martin Luther himself was such a terrible antisemite, and yet why would somebody who hates us so much, want to return Christianity back to our Torah? Martin Luther started out liking us, but then turned against us when we refused to become Christians, and yet I suppose such were the power of his original ideas that they have brought something so positive to our world, namely the United States of America.

Regardless of what the explanation is for all this, what is perhaps the most remarkable part of it is just how much we Jews have influenced the world. Stopping to think about this really helps to put things in perspective. We Jews make up far less than 1% of the world’s population, and yet in a very real way, have had more positive influence in civilizing the world than any other people, no matter how powerful.

And if I may take this a step further, entering the religious realm, I notice that in the greatest, most influential, most universally recognized book ever written, namely our Torah, that G-d devotes only a very tiny percentage of His book talking exclusively about non-Jews as well as the entire, non-human world, and then proceeds to spend the rest of His Torah talking about us Jews. That is probably a pretty good indication that we Jews are indeed the Apple of G-d’s Eye. No matter how much the world may hate us, they simply cannot ignore us.

“It is a reminder that the tzekem Elokim / the image of G-d functions well in many people, giving us something to both respect and to work with.”

Rabbi Emanuel Feldman writes in “Tales out of Shul” (p. 282), that because the word “holocaust” has become trivialized by some to refer to various other prejudices, “it is clear that a non-Jew, even a well-meaning and sympathetic one, can never fully comprehend its meaning”. Later in the chapter (p. 284), he tells of a student who did obtain a significant understanding:

“During a college lecture I was giving on the Holocaust, I noticed a Christian girl silently weeping. After class I asked her if she was all right and if I could help her. She told me that she had never realized what the term “holocaust” meant until that moment. All her life she had known about the persecution of the Jews, but only now did she begin to understand what it was about”.

Ami Magazine also had recently an article about a Polish non-Jew who is dedicated to preserving interest in pre-Holocaust synagogues and cemeteries. There was also concern last year that the new Polish law censoring Holocaust discourse could complicate efforts in arousing interest (see articles in Haaretz , “The Self-appointed, non-Jewish ‘Guardians of Jewish Memory’ in Poland” and in Jerusalem Post, “A Polish Christian Who Preserves Jewish Heritage”).

In 2002, I was on a business trip to Switzerland and Germany, traveling with a non-Jewish associate. We got to our German hotel early enough to take a side trip to Worms, and specifically the area where Rashi once learned. There was an medieval mikveh, plus rebuilt Jewish buildings (the Germans had demolished the original ones in the Nazi era).

See https://www.worms.de/en/tourismus/sehenswertes/listen/synagoge-und-mikwe.php

Other than me, no Jews were around, but they had a small museum with artifacts of Jewish Worms, including a partially burnt Sefer Torah desecrated by Nazis. A movie was showing about former Jewish life in Worms and its sorry end. Groups of German schoolchildren were taken through to get orientation about the Holocaust there.

Too bad most Germans seem to be oblivious nowadays.

The highlight came when I realized it was time for Mincha. The rebuilt shul was open, so we walked over and I davened right there in the sanctuary, near a room where Rashi was said to have studied.

https://www.worms.de/en/tourismus/sehenswertes/juedisches_worms/raschi-und-das-juedische-worms/

You bring back memories of my days as CTO. I always felt weird in Germany. Once davening in my room facing a factory, I could only think it was a crematorium. Walking along the river in Bonn, I was transported back to the days of Rishonim who lived there. Traveling first-class on a bullet train and offered alcoholic beverages, I thought of the trains my relatives were on, fifty years earlier. My trivial and meaningless revenge came when sitting in a negotiation during breaks, with the Germans freely speaking German assuming they would not be understood and staying at a hotel in Vienna where Hitler yms was a bellboy and now a Jew was a (hated) guest.

I was recently in a hardware store on the Upper West Side that was owned by Israelis that had many pictures of Chayalim . The picture that struck me was that of IAF jets flying in formation over Auschwitz. That image is saved on my phone

My grandfather A”H came to the US from Bardejov, then in Hungary and now in Slovakia, around 1900. Descendants of the Divrei Chaim ZY”A of Sanz led the chassidic community that our family there belonged to.

This fine book discusses the Jewish community of Bardejov later in the 20th Century, through its demise at the hands of the Nazis:

https://www.amazon.com/Markus-Planter-Trees-Elizabeth-Liener-ebook/dp/B0792X9GYP/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1549832434&sr=1-1&keywords=markus+trees

The Jewish communal buildings there are now under extensive renovation, but no Jews remain, to my knowledge.

http://bardejov.org/a/jewish-bardejov/bardejov-jewish-history/

http://bardejov.org/a/jewish-bardejov/jewish-suburbia/

http://www.slovak-jewish-heritage.org/bardejov-old-synagogue-compound.html

http://suburbiumbardejov.sk/en/o-projekte/podrobnosti/