Was Michelangelo a Philo-Semite?

Ami Magazine’s (enormous) Sukkos issue includes an interview with Rabbi Benjamin Blech, co-author (with Roy Doliner) the book The Sistine Secrets, and an article about the book.

Michelangelo lived at a time when the Catholic Church was increasing its oppression of Jews — he painted the Sistine Chapel in between the Spanish Inquisition and the Portuguese. He was commissioned to paint the chapel with Christian scenes, but petitioned for liberty to do basically as he wished — and the result is almost entirely drawn from the Jewish Bible, emphasizing the connection between the Church and the Jewish nation.

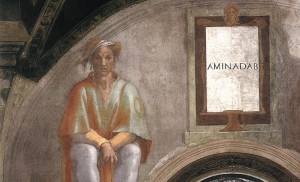

And here, quoted verbatim, is the most surprising find, concerning the painting of Aminadab, who is found in the Book of Exodus only as the father of Nachshon ben Aminadab, prince of the tribe of Yehudah:

Near the end of his torturous years of frescoing, Michelangelo was painting right over the elevated area where the Pope would sit on his gilded throne. There he placed a portrait of Aminadab, a seemingly strange choice since Aminadab was far from a major biblical hero. On Aminadab’s upper left arm we clearly see a bright yellow circle, a ring of cloth that has been sewn onto his garment. This is the exact badge of shame that the Fourth Lateran Council and the Inquisition had forced upon the Jews of Europe. Michelangelo placed this powerful illustration of anti-Semitism on Aminadab, whose name in Hebrew means “from my people, a Prince.” To the Catholic Church, that phrase could mean only one person: the founder of Christianity. Yet here, directly over the head of the Pope, Michelangelo pointed out exactly how the hatred and persecution of the Catholic Church was treating its founder’s relatives! His hidden agenda was to remind the church that its roots were grounded in the Bible given to the Jewish people, and that to ignore this truth was to falsify their religion.

Was Michelangelo the precursor of CUFI, and other pro-Israel Christian groups?

There are several flaws with R’ Blech’s argument that I noticed when his book first came out. In this case, Aminadav is there for one reason: The sides of the ceiling feature all of the (supposed) ancestors of Jesus. Since his line runs through David and Yehuda, Aminadav is there. (There are different lists at the beginning of two of the Gospels. Of course, according to Christian belief, Jesus was *not* the son of Joseph, so this is all meaningless, but that’s another story.)

That’s not to say that Michelangelo was not a lot more pro-Jewish than you would have expected. For example, he used Jews from Rome’s ghetto as models for his Biblical figures (including his statue of Jesus himself), because he felt, logically, that those figures must have looked, well, Jewish. Christian artists since well before him and up until today prefer to pretend that Jesus and all Biblical figures were blonde Nordic types.

The infamous horns on his statue of Moses are not, as is sometimes believed, anti-Semitic. Michelangelo knew full well that the “horns” seen on pictures of Moshe since the Middle Ages were a result of a mistranslation and stuck them there because he really didn’t like the pope whose grave he was making the statue for. (The pope caught on and had it moved somewhere else.)

Funny story: When Jerusalem celebrated the 3,000th anniversary of its capture by King David about twenty years ago, Italy announced it would presenting a gift of copy of a statue of David to the city. This caused officials to panic, because they were worried that meant Michelangelo’s version, which is, ahem, not very tzanua. (Other famous statues of David are similar, taking a bit literally his lack of armor when he faced Goliath.) They ended up presenting a copy of one of the famous clothed versions, though, so everyone was happy; it’s on display at Migdal David. (The same thing happened when Paris decided to give a gift and much to everyone’s relief gave a fountain.)