Dawkins and Friends on Atheism

Scrawled on a wall: “G-d is Dead.” – Nietzsche.

Underneath: “Nietzsche is Dead.” – G-d.

Many years ago, I found it necessary (or so I thought) as a young kiruv (outreach)worker to learn what the other side believed. I picked up Bertrand Russell’s small collection of essays on atheism, and ploughed through them. They wound up enhancing my emunah (belief). This was the best the atheists could cobble together, I thought?

Richard Dawkins, preeminent biologist and spokesperson for contemporary evolutionary thought, is on tour of the US, hawking The G-d Delusion, his new book exposing belief in a Deity as the underlying cause of most of what is wrong with civilization.

Here are two treatments of atheism worthwhile reading.

I know of no more convincing or articulate voice for belief in our generation than Chief Rabbi Jonathan Sacks. This from a recent essay:

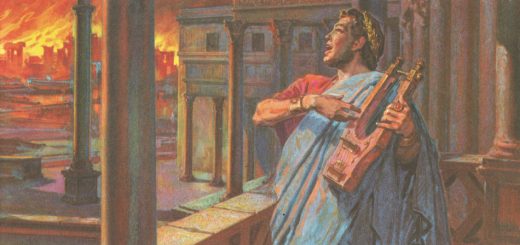

Richard Dawkins is one of the great atheists of our time, and his latest book, The God Delusion, is his angriest. Imagine, he says, a world with no 9/11, no 7/7, no Crusades, no witch-hunts, no Gunpowder Plot, no Indian Partition, no Bosnian massacres, no religious persecution of the Jews, no Northern Ireland troubles, and so on. No religion, therefore no evil in the name of God.

This is good, honest, challenging atheism. I only wish I had as much faith as the learned professor. It would be nice to believe that if you cured people of believing in God, you would thereby have cured them of hate, violence, anger, injustice, cruelty and the urge to control, exploit, dominate and oppress. Nothing in history suggests such a thing. On the contrary, if people do not commit evil in the name of God they have never been short of other reasons to do so: race, the war of classes, the political system, the march of progress, the Darwinian struggle to survive.

In the perennial battle between our lowest and highest instincts, which is the human condition whether we are atheist or believer, people usually robe their most brutal acts in the mantle of high ideals. In this respect the history of religion, like the history of substitutes for religion, is all too human.

There is, though, another thought-experiment worth performing. Imagine a world with no Book of Psalms, no Isaiah, no Ten Commandments, none of Michelangelo’s religious art or Bach’s devotional music, no Dante, no Milton, no medieval cathedrals, no prayer. Imagine one with no narrative like the Exodus to give hope to the oppressed and enslaved. And that really is the point.It took an even greater atheist, Nietzsche, to see the truth with fearless clarity. He called Judaism and Christianity “the slave revolt in morals”. It was, he believed, the ethic of the underdog, the weak, the vulnerable, the powerless. It generated an entirely new set of virtues: “Pity, the kind and helping hand, the warm heart, patience, industriousness, humility, friendliness.”

Nietzsche was contemptuous of such attitudes. Wherever they prevail, he said, “language exhibits a tendency to bring the words ‘good’ and ‘stupid’ closer to each other”. Only slaves are foolish enough to believe that love and gentleness are ways to live. Masters know a different ethic entirely: “According to master morality it is precisely the ‘good’ who inspire fear and want to inspire it.”

On this Nietzsche agrees with Machiavelli, who said that in politics it is better to be feared than to be loved. And here we arrive at the heart of the matter. Nietzsche’s supreme value was the “will to power”.

Look at Dawkins’s list of crimes committed in the name of God and you will see that they are all cases in which religion has been used to conquer, control or intimidate. They are all expressions of the will to power. This, if anything, is the root of all evil, whether it takes religious or secular forms. That is why the supreme virtue of Judaism and Christianity is humility, the opposite of the will to power.

To seek to impose your will on another, against his or her will, is the first step on the road to dehumanisation. It leads people to kill in the name of the God of life, hate in the name of the God of love, and wage war in the name of the God of peace. If Richard Dawkins has done no more than warn us of this danger, then may he forgive me for saying that he is a fine example of why God creates atheists and why sometimes theirs is a prophetic voice.

I have gained much through the years reading the long and deep analyses of Rabbi Shalom Carmy, the master of Torah and philosophy on this side of the pond. Here are a few paragraphs from a published essay of his on smug and self-confident atheism:

I do not know what is true. I do not know the meaning of the universe. But in the midst of doubt, in the collapse of creeds, there is one thing I do not doubt, that no man who lives in the same world with most of us can doubt, and that is that the faith is true and adorable which leads a soldier to throw away his life in obedience to a blindly accepted duty, in a cause which he little understands, in a plan of campaign of which he has no notion, under tactics of which he does not see the use.

The confident skepticism of these words assures us that this is no mad mullah haranguing barefoot tribal youth. We are not in the paradise-promising courtyard of some primitive madrasah. It is springtime at Harvard, and the speaker is Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., who has already ascended from his distinguished professorship of law to his unequalled judicial career, to be capped by thirty years on the Supreme Court of the United States.9 No longer venerated uncritically in liberal circles today, he is still a towering figure in the secular pantheon, “with a

capacity to mold ancient principles to present needs, unique in range and remarkable in prophetic power” (to cite Franklin Roosevelt’s eulogy for him). More important for us: Holmes is perhaps the most unrelenting secularist among America’s leading intellectual-political lights. He stands for hardheaded pragmatism, fully emancipated from Christianity, untouched by lingering aftereffects of religious training.The secular gospel Holmes preaches is the unadulterated cult of

death. The Civil War that led his commander-in-chief to speak of the horrors of divine justice incubated in Holmes a very different faith. Like most of us, Holmes is a member of the materially comfortable classes. Hence the selfish passions of war—plunder, power, rage and rape that formed the soldier’s faith in days of yore, cannot suffice. Nor can he believe in truth and transcendent meaning, the higher passions that rightly or wrongly inspired idealistic (or ideological) warriors justice,

national predominance, preserving the Union or abolishing slavery.Dismayed that “the aspirations of the world are those of commerce,” haunted nonetheless by the instinctive aristocratic conviction that there is a grandeur to human existence that is above the routine of getting and spending, bereft of any sense of transcendent purpose, he is abandoned to reheated chivalry and nihilistic adoration for the blind waste of human life. Like a religious believer he understands that a life is not worth living if one is not willing to die for it, but he strives to avoid the

obverse truth: it is not worth dying for a life that is not worth living.Hence he is not above comparing the “divine” message of war with that of sport: “If once in a while in our rough riding a neck is broken, I regard it, not as a waste, but as a price well paid for the breeding of a race fit for hardship and command.” Secular, rational thought has filled the vacuum and provided a raison d’être for this cultivated, desperate Harvard eminence, where religious dogma might have provided a more useful, sober form of patriotism.

[Thanks of Martin Brody for the Jonathan Sacks piece. I later found it on Hirhurim, the only blog I read religiously. It provided the Shalom Carmy link.]

For a more representative sample of atheistic thought, see http://www.churchoffreethought.org.

Disclaimer: I used to me a member, and some of my writings are on the site.

Thank you for quoting Chief Rabbi Sacks’ eloquent essay that appeared in The (London) Times. However, wouldn’t it have been just as worthwhile to have included that part of the essay in which he relates the story of a rabbi’s justification for the existence of atheists? Not only would this put his concluding paragraph in context but it is a valuable message for all of us who, feeling besieged by secular and antisemitic forces, may slip into intemperance.

Many years ago, I found it necessary (or so I thought) as a young kiruv (outreach)worker to learn what the other side believed. I picked up Bertrand Russell’s small collection of essays on atheism…

I’m afraid that if you want to know what the current generation believes, you’re going to have to throw away all of your books. It’s pure decadence these days, nothing more. Dawkins is preaching to the tiny minority of already converted that actually reads works on such a subject.

> This was the best the atheists could cobble together?

No, actually, it is not. I highly recommend that you read the book Unintelligent Design by Mark Perakh. It makes a very convincing case against organized religion and the so called “proofs” for G-d’s existence. As I am an agnostic (despite an outwardly chareidi lifestyle), I can assure you that the atheists are not as illogical as you present them.

Points well made. Those who, above all, want power will use any available means to get it, even means whose proper use would be beneficial.

Dawkins seems to share the pleasant fantasy that evil would disappear if we just got rid of something in the human condition. While I can’t prove that this is wrong, I believe that the USSR, may it rest in pieces, proved that removing religion is not the answer.

In theory, it was a secular, atheistic society. In practice, Communism quickly became a state religion that made Spanish Catholicism in the 1500s look good.

You remind me of a poster my brother made when he was a kid, and hung on his wall. It was a take-off on the famous book, “This is My G-d,” by Herman Wouk.

My brother’s sign said, “This is My Herman” and was signed, “G-d.”

Shmuel (#4), there is hope for you, too. Don’t be satisfied with your lack of answers so far.

I don’t think it’s the will to power that creates these problems.

It is the will to power at the expense of others. There is a certain fiction that power is like beans in a bucket, and once a certain amount of power is held, the bucket is empty. In this view, you can only have power by taking it from others. I don’t believe this is the truth.

But it is entirely possible to want power, and to exert effort toward achieving it, without deliberately infringing on the rights of others. I don’t see any problem with that. Power is a voluntary concept, in the end; others hold power over you because you consent to allow it, and you hold power over others because they consent to allow it. Once this is understood, power becomes a non-competitive subject, and no longer occupies much of your concern.

Dear Rabbi Adlerstein,

You cleverly neglected to admit not having read Dawkins latest book, or perhaps any of them. Please write another post once you have. The arguments you cited are merely straw man arguments that evil would still exist even with atheism. Yet, you fail to address the fact that religion has lead to a net increase in violence, murder and mayhem. Religions have multiplied violent acts in many ways, 9/11 and suicide bombers in Israel/Iraq being the best recent examples of this.

Moreover, as a Rabbi, you no doubt believe the Torah account of the Flood to be a true one. You must then acknowledge that God himself killed many more people (along with all terrestrial wildlife)in the Flood and later sanctioned more genocides (of the hittites, jebusites, amorites, sodomites, et al.) than Hitler, Stalin, Bin laden, Pol Pot, Hussein, et al. combined!

I know the answer, it was morally perfect when god killed these people, right? Therein lies the exact problem Dawkins is addressing in his book. Again, please read it and re-post.

“Yet, you fail to address the fact that religion has lead to a net increase in violence, murder and mayhem.”

Say what? When was society ever irreligious and peacful such that religion should increase the level of violence? ALL historic human society was religious until very recently. So all societal violence was by definition religious violence. But so what? There were not secular societies existant that would allow the violence to be anything other than religious. We do not find that modern secularists are less violent.